In the 1960s, Lebanon occupied a rare place in the global imagination. It was modern yet ancient, Western-facing yet unmistakably Eastern, glamorous without being rigidly defined. For filmmakers from Europe, America, and Asia, Lebanon became a natural crossroads: a cinematic meeting point where espionage thrillers, romantic dramas, and international adventures could unfold against a backdrop that felt both different and familiar. It helped that the local population had one of the highest per-capita cinema attendance rates worldwide in 1960, according to UNESCO, creating a large and enthusiastic audience for both local and international films. Alongside this international visibility, a rich local film culture was also taking shape, with pioneers like George Nasser leading the charge.

In the 1960s — due to Lebanon’s position as a regional cultural and economic hub with a liberal, laissez-faire economy, excellent technical facilities, and a vibrant cultural scene — this international presence crystallized into a remarkable moment when world cinema found a home in Lebanon.

Beirut as the Mediterranean Dream

Early 1960s productions often depicted Lebanon as a sunlit Mediterranean paradise. Films like Mediterranean Holiday (1962) and Crucero de Verano (1964) positioned Beirut within a larger leisure circuit of Southern Europe and the Mediterranean. The country appeared elegant and cosmopolitan — a place where cruise ships docked, languages overlapped, and cultures mixed effortlessly.

These films aligned Lebanon with freedom of movement and cosmopolitan sensibilities, positioning it alongside Rome, Athens, and the French Riviera rather than isolating it as an “Eastern” other. For many Lebanese audiences, these films were a form of entertainment and escapism, offering a glamorous and adventurous view of their homeland.

The Spy Capital of the Cold War

By the mid-1960s, Lebanon’s role in cinema shifted. Beirut became a favored setting for Cold War spy thrillers, its neutrality and international flavor making it ideal for secret agents and double-crosses.

A significant number of espionage films either took place in Beirut or used it as a central hub: Last Plane to Baalbek (also known as Operation Baalbeck) (1964), Secret Agent Fireball (1965), 24 Hours to Kill (1965), Man on the Spying Trapeze (1966), Spies Strike Silently (1966), Agent 505 – Todesfalle Beirut (1966), Il marchio di Kriminal (1967). Airports, hotels, and casinos became familiar sites of intrigue.

Italian and pan-European productions, including Secret Agent 777 – Operazione Mistero (1965), and Agent 3S3: Passport to Hell (1965), Il Cobra (1967), L’uomo del colpo perfetto (1967), and Flashman (1967), placed Beirut squarely in the Eurospy boom, treating it not as an exotic exception but as a familiar node in a global network of conspiracy — interchangeable with Rome, Istanbul, or Hong Kong.

Unlike the more rigid and colder atmospheres of Berlin or Moscow, Beirut was fluid and unpredictable. Where the Spies Are (1965), starring David Niven — best known for A Matter of Life and Death (1946) — exemplified this, blending espionage with wit and cosmopolitan ease.

Niven’s urbane, detached persona complemented the city’s shifting allegiances and constant motion. Though not free from orientalist tropes, these films positioned Beirut as a modern crossroads rather than a purely exotic construct.

French Cinema and the Beirut of Ambiguity

French cinema brought a different sensibility. Rather than focusing on global conspiracies, filmmakers explored individual drift, chance encounters, and emotional instability. Beirut became a psychological landscape.

Backfire! (1964) starred Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg, whose New Wave personas — ironic, mobile, and observant — fit seamlessly into the city’s unsettled atmosphere.

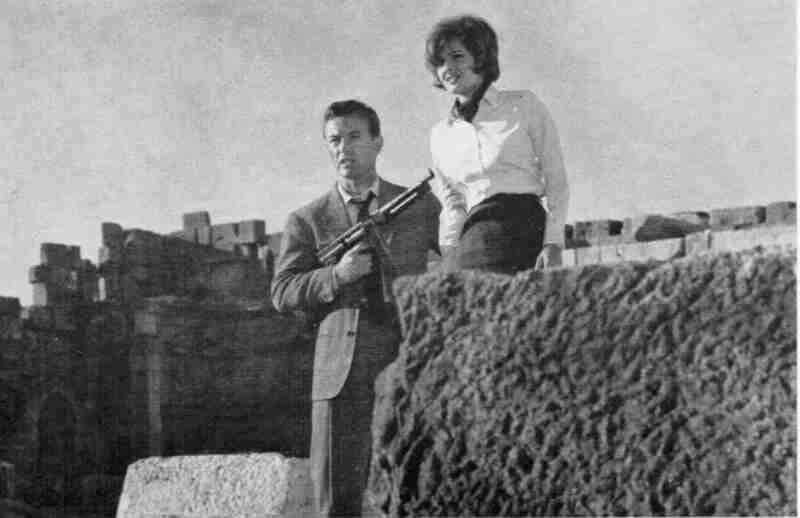

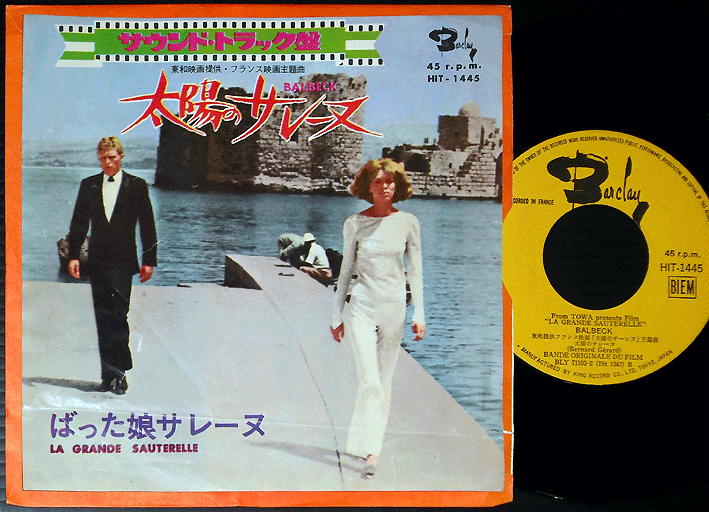

In La Grande Sauterelle (1967), Mireille Darc transformed Beirut into a space of tension, where lives intersected briefly before moving on. Together, these films anchor Beirut within aesthetics of 1960s European modernist cinema: often mobile, uncertain, and emotionally complex.

Anglo-European Cinema

Beirut also attracted actors from a changing European cinema. David Hemmings, emerging from Blow-Up (1966), embodied modern alienation in Only When I Larf (1968), aligning with Beirut’s ambiguous urban identity. Richard Attenborough’s mid-1960s role in the same movie echoed Beirut’s function as a global city and a space of passage.

These actors embodied a cinematic era defined by dislocation and changing moral centers. Beirut, with its international tempo, fit effortlessly into this visual language.

Beirut and South Asian Cinema — A Transnational Screen

Beirut’s cinematic role wasn’t confined to Europe and America. It also became an important setting for South Asian cinema, where the city functioned as a globally legible backdrop.

In 1967, Rishta Hai Pyar Ka became widely regarded as the first Pakistani film shot outside Pakistan. Its production in Beirut reflected the city’s accessibility and neutrality, a space where romance and aspiration could unfold beyond national borders.

That same year, the Indian movie An Evening in Paris (1967) famously used Beirut to represent Paris itself. Beirut’s modern architecture and Mediterranean charm made it a convincing European fantasy.

The Indian film industry revisited the country with Ankhen (1968), where Beirut served as a site of glamour and intrigue. These South Asian films highlight Beirut’s unique role in world cinema, not just as a destination, but as a transnational cinematic space transcending national boundaries between East and West.

Casinos, Crime, and the City at Night

By the late 1960s, Beirut’s reputation for risk and luxury was crystallized in films like Rebus/Appointment in Beirut (1968), centered on a casino crime syndicate. Gambling tables, shadowed lounges, and international criminals reinforced Beirut as a city where fortunes could be made, or lost, overnight.

Beyond the 1960s — The Last International Glimpses

Though the 1960s were Beirut’s most concentrated period in global cinema, the early 1970s extended its visibility with a darker edge. Films like Embassy (1972), Mafia Junction (1973), and Honeybaby Honeybaby (1974), retained Cold War intrigue, and offered fleeting glimpses of Beirut before 1975.

These films act as a coda: the final moments in which Beirut appeared in international cinema as a site of suspense, rather than imminent rupture.

A Moment Preserved on Film

To revisit these works today is not nostalgia, but cultural reclamation — recovering a moment when Lebanon appeared in global cinema as an international hub, not as a metaphor of crisis. What makes this cinematic moment so poignant is hindsight itself. The Beirut preserved in these films — open, confident, globally connected — would soon be irrevocably altered.

On April 13, 1975, the Lebanese Civil War began, disrupting the city’s role as a crossroads for international cinema for years to come. Around this time, filmmaker Georges Chamchoum released Lebanon... Why? while Maroun Baghdadi released Beirut ya Beirut, turning the camera inward toward the city’s contradictions, hopes, and unfinished futures. Through them and several others, a shift was made: from Beirut as a site through which the world passed, to Beirut speaking for itself. But that’s another story.