On the northern slopes of the Aurès Mountains in northeastern Algeria lie the ruins of Timgad, one of the most complete and informative examples of Roman urban planning outside Italy. Founded around 100 CE under the emperor Trajan, this city — known in antiquity as Colonia Marciana Ulpia Traiana Thamugadi — was designed as a settlement for military veterans and evolved into a significant civic center in Roman North Africa.

Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982, Timgad provides valuable insights into the architectural principles, public spaces, and civic life of a Roman colonial town. Its preservation allows contemporary audiences to observe how urban order, monumentality, and daily life were integrated into a coherent spatial system.

A Grid for Life and Function

Timgad stands out among ancient cities for being planned “ex nihilo” — built on a previously unoccupied site rather than developing gradually over centuries. This deliberate foundation reflects broader Roman ideals of rationality, organization, and civic structure.

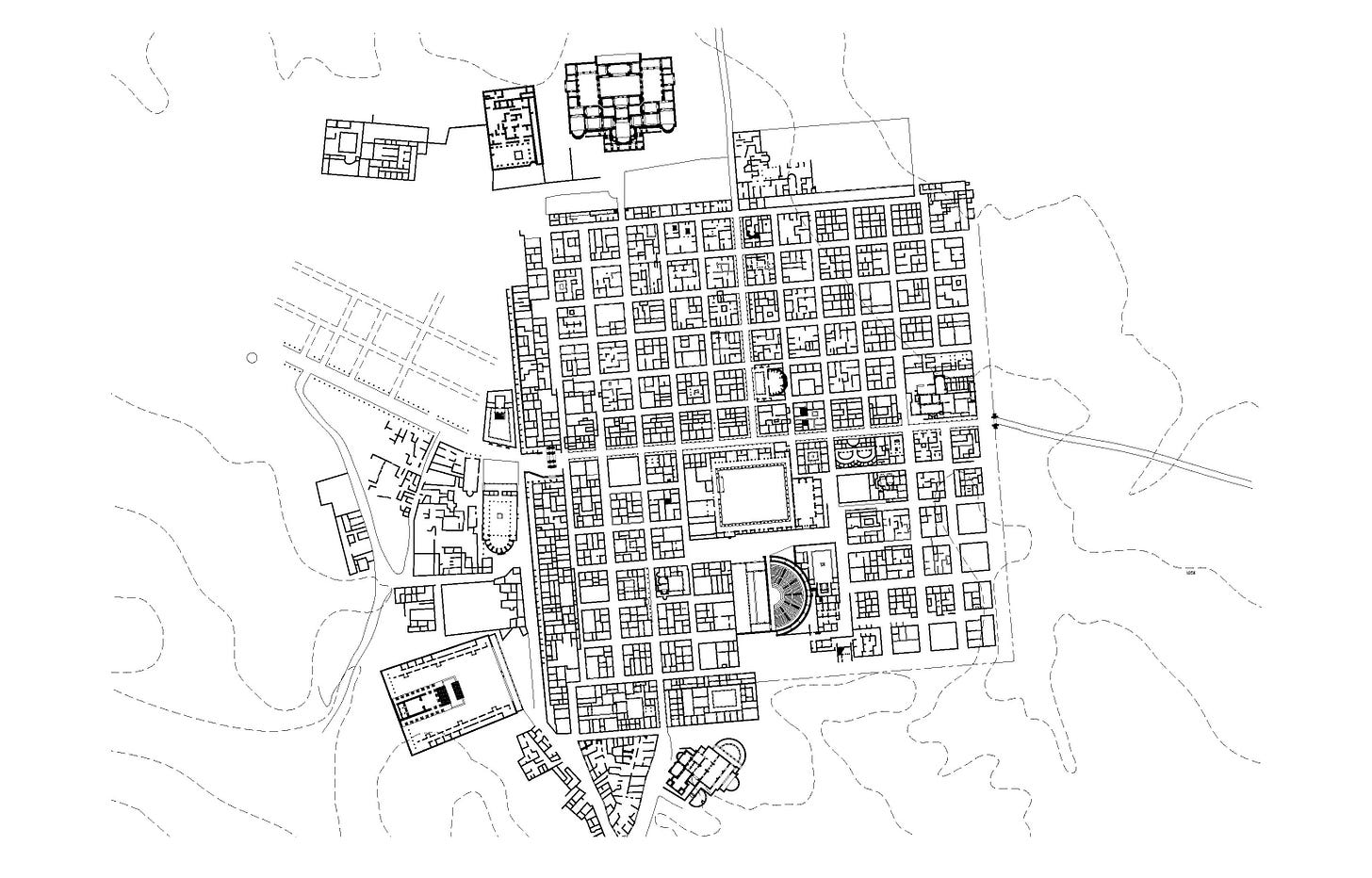

The city’s layout follows a rigid orthogonal grid structured around two principal axes: the cardo maximus running north–south and the decumanus maximus running east–west. These main streets intersected at the forum, dividing the settlement into regular blocks that structured movement, commerce, and residential life. The clarity of this design still makes Timgad a reference point in discussions of Roman town planning.

The grid system was not purely technical. It represented a spatial expression of Roman administrative and civic ideals. Streets were proportioned for circulation and access, while public institutions were positioned at prominent intersections, ensuring visibility and accessibility. In this way, the city’s design reveals how architecture and urban planning were instruments of social organization.

Public Space and Structures of Civic Life

At the western end of the decumanus maximus stands the Arch of Trajan, a monumental triple-arched gateway approximately 12 meters high. Constructed in sandstone and decorated with Corinthian columns, the arch functioned as a ceremonial entrance and as a marker of imperial authority within the urban landscape.

At the center of the city lies the forum, the principal civic space of Timgad. Surrounded by administrative buildings and temples, it served as the location for public assemblies, commercial exchange, and official ceremonies. Its position at the intersection of the two main streets demonstrates how civic and spatial organization were closely aligned.

Nearby, the theatre illustrates the cultural dimension of Roman urban life. Built into the natural slope of the terrain, it accommodated several thousand spectators and functioned as a venue for drama, public events, and communal gatherings. The theatre highlights the importance of performance and shared experience within the civic framework of the city.

Timgad also included public baths, temples, basilicas, and a library. The presence of a public library is particularly notable, as it indicates the role of literary culture and education within the community. Inscriptions discovered at the site reference benefactors who financed such civic amenities, reflecting the Roman practice of local patronage and public philanthropy.

Art and Material Culture

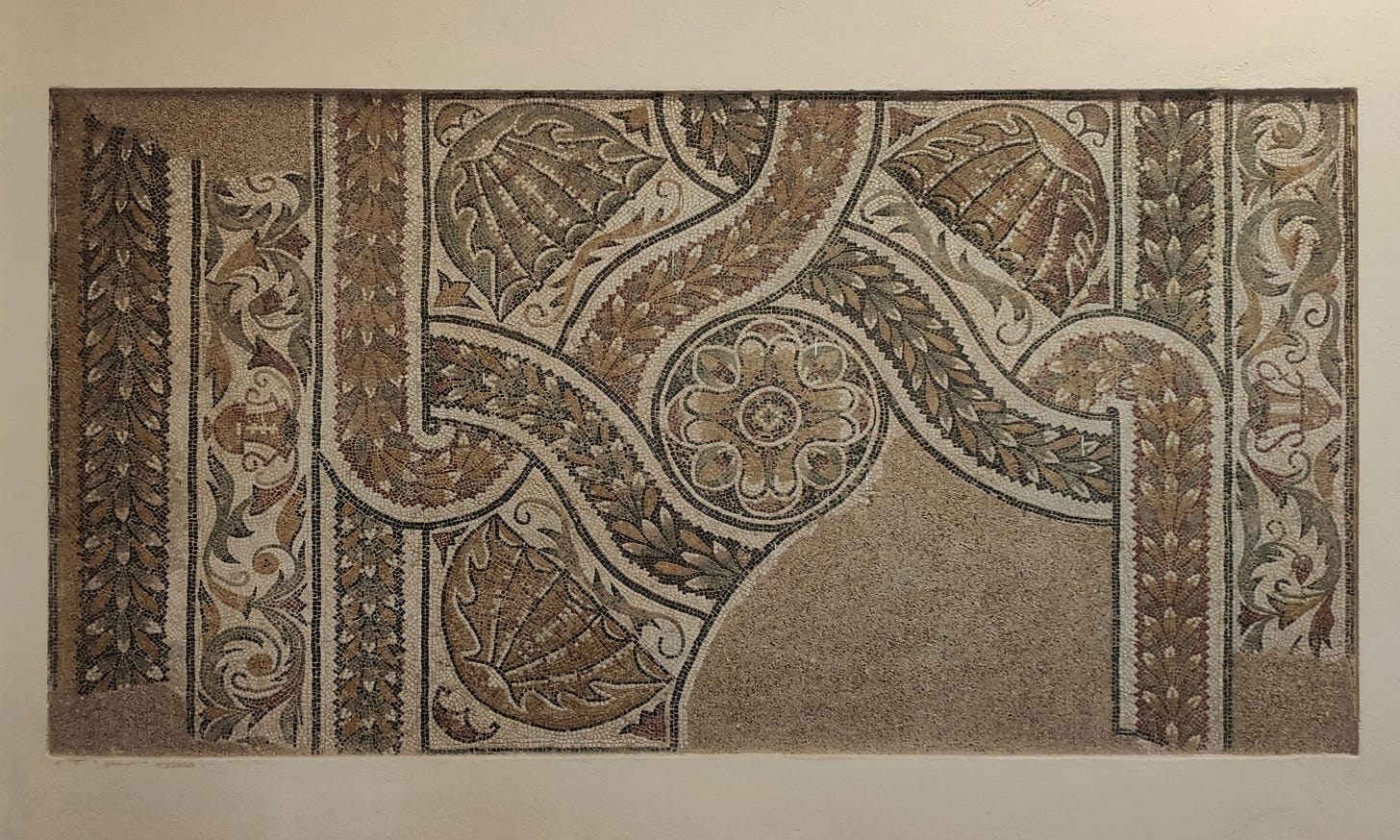

Archaeological research has documented mosaics, inscriptions, and architectural decoration that shed light on artistic production in Timgad. Mosaic floors discovered in private houses and bath complexes demonstrate the diffusion of Mediterranean decorative traditions into North Africa. These works often combined geometric patterns with figurative motifs, revealing both technical skill and regional adaptation.

Inscriptions found throughout the city provide additional insight into civic identity and social structure. They record dedications, public donations, and administrative functions, offering a detailed picture of how architecture and art were embedded within broader social systems. Through these material traces, Timgad emerges not only as a military colony but as a functioning urban community with cultural and intellectual dimensions.

Transformation and Decline

Although initially established as a veteran colony, Timgad expanded beyond its original walls as its population grew. Over the centuries, the city adapted to political and religious change. By the 4th century CE, it had become an important center of Christian activity, reflecting the wider transformation of the Roman Empire during Late Antiquity.

The city’s decline followed a series of regional upheavals. The Vandal invasions of the 5th century disrupted urban life, and although Byzantine forces later regained control and constructed defensive works nearby, Timgad never fully recovered its earlier prominence. Following the Arab conquests of North Africa in the 7th and early 8th centuries, the settlement was gradually abandoned. Covered by sand and largely untouched by later construction, its remains were preserved in unusual clarity.

Preservation and Contemporary Relevance

Systematic excavations began in the late 19th century, revealing an exceptionally well-preserved Roman grid and architectural ensemble. Because Timgad was not significantly reoccupied after antiquity, its original layout and many structural elements survived without the layering typical of continuously inhabited cities.

Today, Timgad remains a valuable case study for scholars of architecture, archaeology, and heritage conservation. It illustrates how urban form reflects cultural values, how monumental and everyday architecture coexist within a single system, and how material remains continue to inform contemporary discussions about preservation and identity. In the broader Mediterranean context, Timgad underscores the interconnected histories of North Africa and the Roman world, offering a tangible reminder of how architecture can serve both practical needs and cultural expression across centuries.