The Traditional Architecture of Tunisia — A Living Legacy of Culture and Climate

By Ralph I. Hage, Editor

In Tunisia, architecture is more than shelter – it’s a record of civilizations, a tool for survival, and a reflection of identity. From the busy medinas of the north to the sun-scorched ksour of the south, Tunisia’s traditional architecture tells stories of adaptation, faith, community, and innovation. Shaped by geography and history, these structures are part of a living heritage that continues to influence how Tunisians build and live today.

Fortresses of Faith – The Ribats of the Coast

The Islamic conquest of North Africa in the 7th century introduced not just a new religion, but also a new architectural vocabulary. Among the most iconic early Islamic buildings in Tunisia are the ribats – fortified religious outposts that served both as military defenses and spiritual retreats.

The Ribat of Monastir, dating to 796 CE, is one of the oldest surviving Islamic monuments in North Africa. With its stone walls, corner towers, and central courtyard, it was designed to repel invaders while accommodating ascetic warrior-monks. Nearby, the Ribat of Sousse, rebuilt in the early 9th century, features similar defensive elements along with North Africa’s earliest known example of a dome on squinches – a significant architectural innovation. These ribats weren’t isolated. They formed part of a broader system of coastal defenses, many of which are integrated into the medinas of Tunisia’s historic cities – compact, walled urban centers filled with winding alleys, souks, and religious sites.

The Dar – Domestic Harmony in the Medina

Wander through the medina of Tunis, and you’ll find a seemingly chaotic maze of alleys. But behind the unassuming doorways lie some of Tunisia’s most remarkable spaces: the traditional houses known as dars. These homes, often passed down through generations, are marvels of climate-sensitive design and cultural expression.

At the heart of the dar is the sahn, or an open-air courtyard that serves as the social and thermal core of the house. Surrounded by rooms on all sides, the courtyard allows light and air to circulate while maintaining complete privacy, in keeping with Islamic social values. Thick whitewashed walls, high ceilings, and shaded arcades moderate temperatures, keeping interiors cool in the blazing summer heat.

Upper levels often feature mashrabiya – latticed wooden screens that allow women to observe the street without being seen. These architectural elements, which originated in the eastern Islamic world, took on a distinctly North African character in Tunisia’s medinas.

Caravanserais, Souks, and Hammams – Urban Architecture at Work

The traditional Tunisian city was not just a place to live – it was a dynamic hub of commerce and community. The caravanserais of cities like Sfax and Kairouan served as inns for traveling merchants, with ground floors for animals and storage, and upper stories for lodging. Many were built from stone, with arched porticoes surrounding open courtyards.

Souks, or covered markets, feature vaulted ceilings and narrow walkways designed to shield merchants and shoppers from the sun. Nearby, hammams (or public baths) with domed roofs and star-shaped skylights provided essential hygiene and social interaction, especially before modern plumbing.

Together, these structures formed the beating heart of the medina – spaces that were both functional and deeply tied to the rhythms of daily life.

Survival by Design – Southern Tunisia’s Ksour and Troglodyte Homes

In the arid south, where summer temperatures can soar above 45°C (113°F), architecture had to evolve. The solutions that emerged were ingenious.

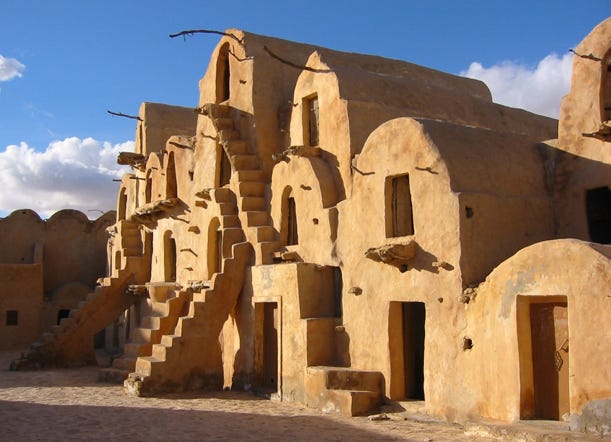

The ksar (plural ksour) is a fortified granary village. Built from local stone and earth, these structures feature multiple levels of vaulted storage cells called ghorfas, often arranged around a central courtyard. They were used to store grain and protect it from raiders, but also served as seasonal residences. Notable examples include Ksar Ouled Soltane and Chenini, some of which date back to the 15th century.

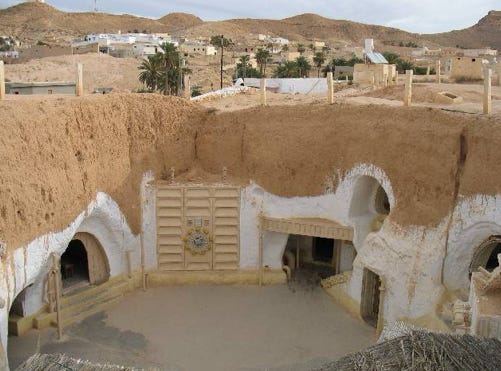

Equally fascinating are the troglodyte homes of Matmata. Carved into the soft rock of the Dahar plateau, these subterranean dwellings feature a central pit, with rooms dug into the surrounding walls. Their design ensures thermal insulation, with cool interiors in summer and warmth in winter – long before air conditioning was invented. Some of these homes are still inhabited today, while others have become guesthouses and tourist attractions. One even famously served as Luke Skywalker’s home in Star Wars.

Ottoman Influence and Colonial Contrasts

From the 16th to the 19th century, Tunisia came under Ottoman influence, and its architecture followed suit. Mosques, palaces, and madrasas from this period are notable for their decorative richness. The Youssef Dey Mosque in Tunis, for instance, features a distinctive octagonal minaret and polychrome tilework, while the palaces of the Husainid Beys display intricate stucco, painted ceilings, and Andalusian-style courtyards.

The French protectorate period (1881–1956) brought European styles to Tunisian cities, introducing Haussmannian boulevards, Art Deco façades, and Neo-Moorish hybrids. These buildings – like the Municipal Theatre of Tunis and the Cathedral of St. Vincent de Paul – reflect a different chapter in Tunisia’s architectural story, one of imposed aesthetics and urban modernization.

A Heritage in Transition

Today, Tunisia’s traditional architecture faces both challenges and opportunities. Urban sprawl, neglect, and climate change threaten many historic structures. In the south, over 40% of ksour are at risk of collapse or abandonment due to rural exodus and lack of restoration funding.

Yet, there is also hope. Restoration projects in medinas, sustainable tourism in troglodyte villages, and contemporary architects reviving vernacular techniques suggest a renewed appreciation for this rich architectural legacy. Guesthouses, cultural centers, and adaptive reuse projects are breathing new life into old structures – bridging the past and present with care and creativity.

A Living Archive of Adaptation

Tunisia’s traditional architecture is not frozen in time. It is an evolving system, born of necessity, nurtured by craftsmanship, and shaped by countless hands over centuries. From the humble courtyard of a family home to the watchtower of a coastal ribat, these structures speak to the human capacity for adaptation, artistry, and resilience.

As Tunisia continues to navigate the pressures of modern life, its architectural heritage offers more than nostalgia – it offers models of sustainability, community, and beauty that are as relevant today as they were a thousand years ago.