There’s a familiar line people like to repeat in Lebanon: wherever you dig, you’ll find ruins. A construction site turns into an archaeological dig. A routine repair exposes an ancient wall. Remove soil from a garden and find a 1,800 year old Roman amphitheater buried below. History is always just beneath the surface.

It’s a comforting idea that suggests continuity. Civilization layered neatly on top of civilization. But it also limits how far back we allow Lebanon’s story to go, because ruins generally assume people. They assume cities, empires, and names we recognize from history class. They imply that relevant history begins when humans start leaving things behind. So it’s worth asking a question — one that almost never comes up when Lebanon’s past is discussed:

Did the land that makes up Lebanon today have dinosaurs? The answer, surprisingly, is yes.

Ninety Million Year Old Footprints

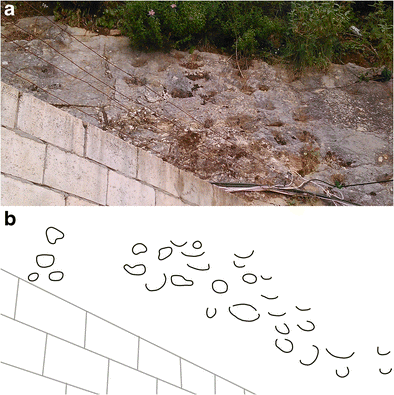

In the hills of Mount Lebanon, along the road between Batha and Ghosta, there are limestone surfaces marked by dinosaur footprints. Not replicas or illustrations, but actual impressions left in soft ground more than ninety million years ago, later hardened into stone.

They’re easy to miss. There are no fences, no dramatic signage. You could drive past them without ever knowing what you’re looking at. But paleontologists who have studied the site describe multiple trackways spread across a broad area — evidence that several dinosaurs crossed this terrain, not just one.

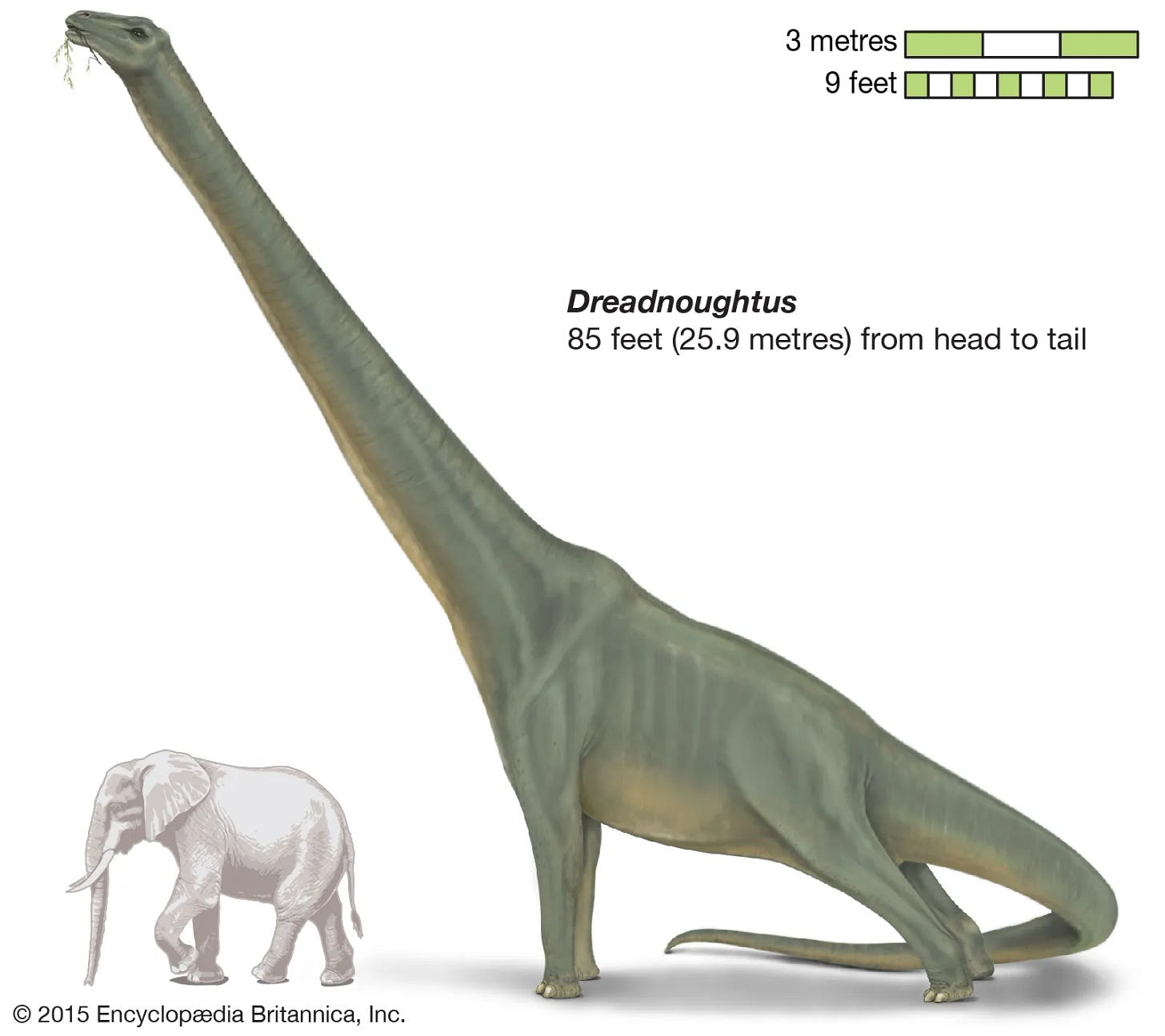

Most of the tracks are attributed to sauropods, the massive, long-necked herbivores that tend to dominate our mental image of dinosaurs. Others may belong to theropods or ornithopods, smaller bipedal dinosaurs whose footprints can be difficult to distinguish from one another.

What matters more than the exact classification is the setting. Dinosaur footprints only form under specific conditions: flat ground, soft sediment, moisture. In other words, the kind of environment we rarely associate with Mount Lebanon today.

Where there are now steep roads and terraced hillsides, there were once coastal flats — low, open landscapes where large animals could walk, pause, and move on. The mountain, as we know it, hadn’t yet become itself.

Teeth in the South

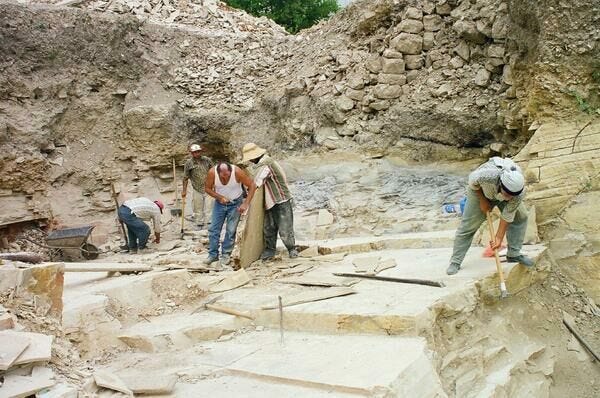

Footprints are one thing. Body fossils are another, and Lebanon has very few of those when it comes to dinosaurs. But in the early 2000s, researchers documented the discovery of two fossilized dinosaur teeth near Jezzine.

They date to the Early Cretaceous period and are believed to belong to brachiosaurid sauropods — enormous plant-eaters with long forelimbs and elevated necks. The kind of animals that required vast amounts of vegetation to survive.

The teeth were found in sandstone deposited by rivers and deltas. Which means that parts of what is now southern Lebanon were once watered plains, shaped by flowing water and capable of supporting animals of astonishing size.

This is an important detail. Lebanon’s prehistoric story is often reduced to one idea: sea. And it’s true that much of the region spent long stretches underwater — but not all of it, and not all at once. Lebanon wasn’t just submerged, it was changing.

Why Dinosaurs Don’t Fit the Story Usually Told

Ask around and most people might tell you Lebanon doesn’t have dinosaur remains. Or that if it did, we would know about it. Dinosaur remans are generally found in places with vast spaces — deserts, plains, or badlands. Not to a small, crowded country better known for human settlement ruins and reinvention.

Part of this has to do with geology. Lebanon is famous among paleontologists for something else entirely: its extraordinary marine fossils. Sites like Haqel and Hjoula preserve fish, rays, crustaceans, and squid from the time when the region lay beneath the ancient Tethys Sea.

These fossils are remarkable in their detail. They’re displayed in museums across Europe and beyond, often admired with little reference to Lebanon itself.

Dinosaurs, by contrast, appear here only briefly and fragmentarily: a footprint that survived just long enough, a tooth carried by a river and buried in sand.

A Land of Margins

During the age of dinosaurs, Lebanon was a place of edges. Shorelines that advanced and retreated, forests that produced amber, rivers that carried sediment — and occasionally teeth — toward the sea.

This matters, not just scientifically but symbolically. The dinosaurs of Lebanon weren’t rulers of a vast interior. They moved through transitional spaces. They crossed landscapes that were always in the process of becoming something else.

Lebanon is often described today as layered, interrupted, and unfinished. Its deeper history suggests those qualities aren’t new. Long before cities and borders, this was a place shaped by instability and change.

What Counts as Heritage

Dinosaur footprints don’t necessarily look like heritage in the way many are accustomed to recognizing it. They don’t rise vertically, announce themselves, or demand attention. That makes them vulnerable to construction, erosion, and simple disregard. But they also offer a different way of thinking about the past. One that isn’t anchored to empire, politics, or monument, but to movement and presence without permanence.

Acknowledging dinosaurs in Lebanon widens the frame of its rich heritage of ruins. It reminds us that this land has held many worlds before it held ours.