The Beirut Apartment that Charles de Gaulle & His Family Called Home

By Ralph I. Hage, Editor

Long before Charles de Gaulle became the Founder of the Modern French Republic, he lived quietly with his family in a rented first-floor Beirut apartment.

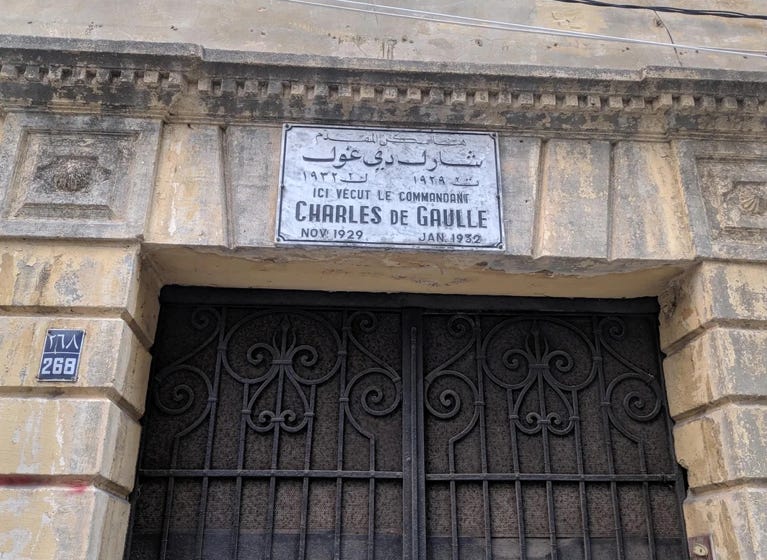

During the early years of the French Mandate in Lebanon, Charles de Gaulle — then a rising military officer and strategist, and not yet the global political figure he would become — was stationed in Beirut. Between 1929 and 1931, he lived with his family on the first floor of a building owned by Elias Wehbe in the Mar Elias neighborhood, a short distance from the Grand Serail where he carried out his duties. It was a traditional Lebanese central-hall typology apartment where a pair of columns flanked each end of the lounge, opened to a large terrace, contained a large dining room, three bedrooms and a spacious bathroom.

A Temporary Home for a Rising Officer

At the time, de Gaulle served as a major on the General Staff of the Levant Troops in Beirut. He was assigned to the intelligence division, or the 2nd Bureau, which included coordinating the military and administrative machinery of the French Mandate — a system imposed on the region after World War I — a structure that combined governance with tight political control. His residence in Mar Elias provided him proximity to the Serail, allowing him to balance demanding working hours with family life in a city undergoing rapid change under French oversight.

The house itself, ordinary by outward appearance, served as the backdrop to an early and relatively quiet phase in de Gaulle’s life — a period not yet acquainted with the magnitude of global war or political leadership.

During this time, he carried out several military missions, gave lectures, wrote a story about the troops of the Levant and other texts that he later included in his 1932 book ‘The Edge of the Sword.’

Offering a counterpoint to his demanding public role, the Mar Elias apartment became the center of a quieter, more private life.

Behind the Uniform

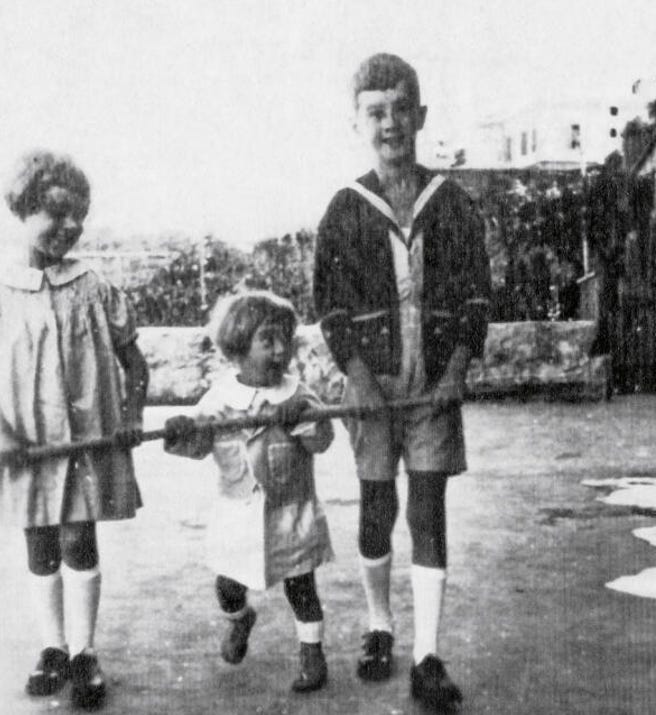

Beyond the political and military context, the Mar Elias residence was also the stage for an intimate chapter in the de Gaulle family’s story. When they moved to Beirut, Charles and his wife Yvonne had three young children, including their youngest, Anne, who had been born only a year before, in 1928. Anne had Down Syndrome, and at a time when children with disabilities were often institutionalized or kept out of public view, the de Gaulles chose to raise her at home.

While de Gaulle spent long hours at the Grand Serail, one can imagine Yvonne caring for baby Anne in the quiet rhythms of daily life — navigating a new environment, tending to her children, and waiting for her husband to return from his duties.

At a time when many prominent families, particularly those in the public eye, chose to keep their children with special needs out of the spotlight, Charles and Yvonne de Gaulle took a markedly different approach. They devoted themselves to their daughter, spending significant time with her and appearing publicly together without concern for public opinion.

Relatives of de Gaulle noted a striking contrast in his behavior toward Anne. Typically reserved and stoic in his expressions of affection, the General was notably more open and playful with his daughter. He would engage her with songs, dances, and pantomimes, offering a side of himself that was rarely seen by the public.

De Gaulle’s Return During World War II

De Gaulle would return to Lebanon during World War II, though under vastly different circumstances. By 1941, he had become the leader of the Free French Forces, navigating the competition and cooperation between French and British influence in the region. His role in the political transformations of that period — including the signing of the Lyttleton–de Gaulle agreement — remains interpreted through very different lenses in Lebanon and the region, often shaped by the complex legacy of the Mandate and its impacts. For many Lebanese, that period was marked as much by uprisings and political restrictions as by the alliances of global war.

A House That Holds Many Histories

The French Mandate itself was an era marked by both developmental ambitions and heavy-handed control, and its memory remains sharply divided in Lebanon.

For many people there, de Gaulle’s presence in the country cannot be separated from the larger history of the Mandate, a period remembered in sharply varied ways. His actions and policies are not universally celebrated — and for many Lebanese, remain deeply contentious.

Yet he is still remembered in some of his phrases — such as “I’m going to the complicated East with simple ideas,” or “doing politics in Lebanon is like stepping on eggs” — not always out of admiration, but because they captured some realities of a region that the French never fully understood.

Others remember some of the stances that he took. While he was president, he condemned Israel for starting the “endless” 1967 war and ordered the embargo of all weapons destined for Israel after they bombed Beirut airport and destroyed its national carrier airplanes. Whatever one’s view of de Gaulle, these positions stood out in a Western landscape increasingly aligned with Israeli military interests.

From Private Residence to Historical Landmark

All things considered, the house in Mar Elias carries a cultural and historical significance that extends beyond political judgment. It is a rare remnant of Beirut’s Mandate-era fabric — a building that witnessed both the official duties of a young officer and the quieter, universal moments of family life. In this sense, the home stands as part of Beirut’s layered memory: not simply a waypoint in the career of a future French president, but also a place where everyday human stories unfolded.

Today, the house in Mar Elias still stands, now owned by the Al-Hoss family, and has long been unoccupied. What was once a dignified residence has now fallen into neglect: the façade is peeling, the structure is not maintained, sits largely abandoned, and is often surrounded by piles of garbage.

Since 2016, it has been officially recognized as a historic building in Lebanon, yet despite its status, it stands forlorn, its distinctive architecture battered by time and disuse. It isn’t just a physical decay: it’s a metaphor for broader neglect of Lebanon’s cultural memory.

La Boisserie

The contrast with La Boisserie, de Gaulle’s meticulously preserved home in Colombey-les-Deux-Églises, could not be sharper. In France, La Boisserie is maintained with reverence — restored, curated, and opened to the public as a place of memory and national reflection. It is not cited to idealize a colonial past, but to illustrate a simple truth: nations must protect the physical vessels of their history, even when that history is complex.

Meanwhile, de Gaulle’s more modest residence in Beirut — a small part of our own multifaceted history — stands in ruin, its walls collapsing as though the memory they carry were somehow unworthy of care. Preserving such sites is not about exalting foreign figures and does not legitimize the Mandate; it contextualizes it — allowing future generations to have access to every chapter of their past.

The House Behind the Photograph

On 22 August 1962, Charles de Gaulle narrowly survived an assassination attempt at Petit-Clamart. It is claimed that the bullet that might have killed him was stopped by the framed photograph of Anne he always carried with him. I never found that photograph, but it isn’t too far-fetched to imagine that its backdrop may have been that very same Beirut apartment they once called home.