The Alawites of the Eastern Mediterranean — Beyond Sect and State

By Ralph I. Hage, Editor

Behind the Label

Few communities in the Middle East have been as misunderstood as the Alawites. Often invoked as a political shorthand or reduced to a sectarian marker, they are more accurately understood as the bearers of a complex religious tradition and a collective memory shaped by centuries of marginalization.

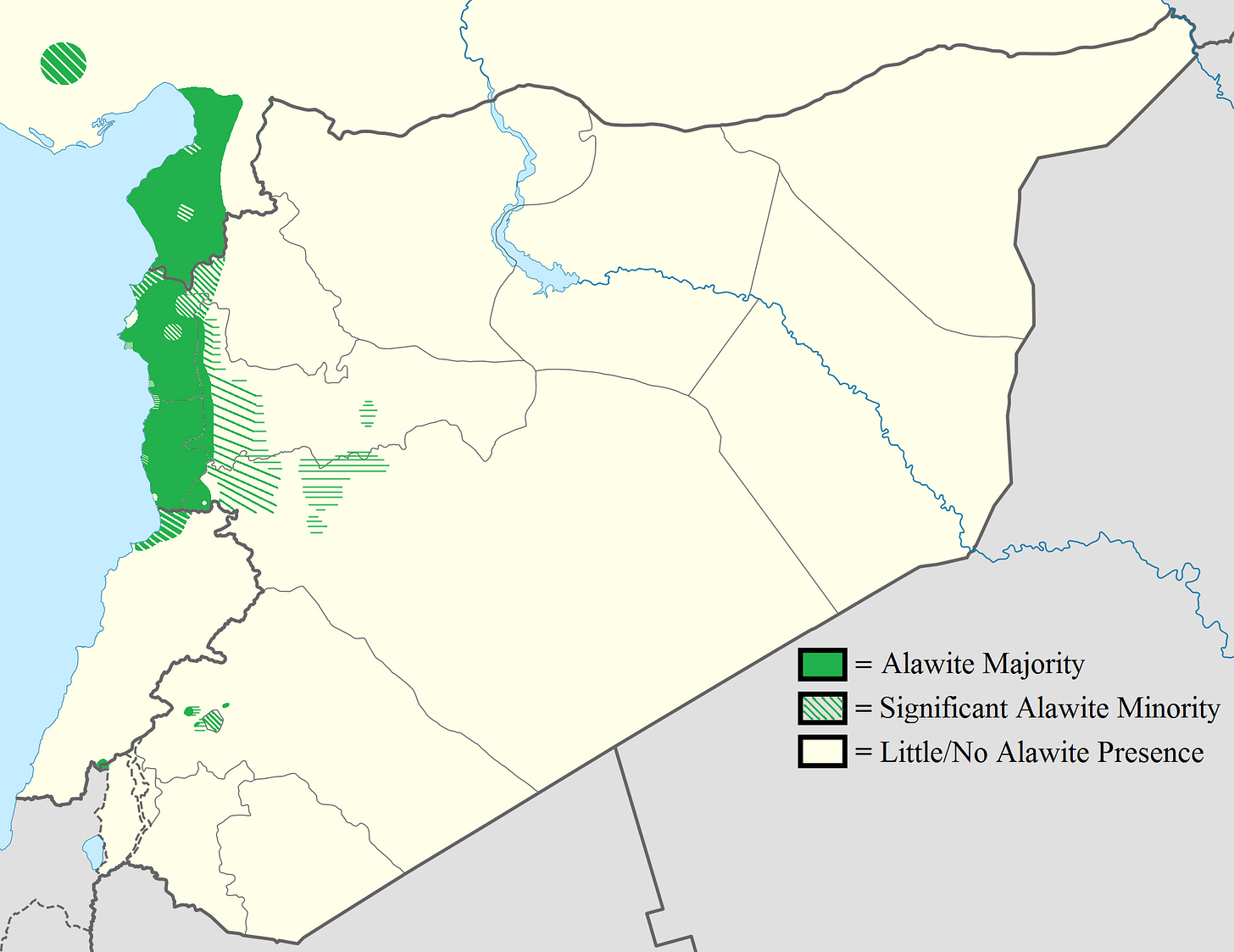

The Alawites — who call themselves ʿAlawiyyūn — are an Arabic-speaking community numbering between two and three million people, concentrated primarily along Syria’s Mediterranean coast, particularly in the Latakia and Tartus regions, with smaller populations in Lebanon and southern Turkey. Their name derives from ʿAli ibn Abi Talib, cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad.

Origins in an Esoteric Age

Alawism emerged during the ninth and tenth centuries, a formative period when early Islamic theology had not yet hardened into fixed orthodoxies. The tradition coalesced around teachings attributed to Muhammad ibn Nusayr, from whom outsiders long referred to the community as “Nusayris” — a term now rejected by Alawites themselves. This was an era of intense intellectual experimentation, when Shi’a mysticism, Greek philosophy, Gnostic symbolism, and local religious customs mingled freely.

From this mix arose a theology that privileged hidden meaning over literal interpretation. Alawite doctrine was never codified in written scripture accessible to all believers; instead, it developed as an initiatory tradition, transmitted orally and selectively. This esotericism would become both a defining feature of Alawite identity and a source of suspicion from surrounding religious authorities.

A Hidden Cosmology

At the heart of Alawite belief lies a symbolic understanding of the divine, often articulated through a triadic framework: maʿna (meaning or essence), ism (name), and bab (gate). In this schema, ʿAli is seen not only as a manifestation of divine essence but as a central figure embodying both divine and human aspects. The Prophet Muhammad is considered the veil or name through which the divine essence is revealed, while Salman al-Farisi, a companion of the Prophet, serves as the gate to esoteric wisdom and knowledge.

Alawite religious practice emphasizes symbolic interpretation over legalistic observance. Rituals like prayer, fasting, and pilgrimage are understood metaphorically, reflecting an inner spirituality rather than formal obligations. The community also holds beliefs such as the transmigration of souls, a concept that places it outside both Sunni and Shi’a orthodoxy. For centuries, these distinctive doctrines led to accusations of heresy, which was used in both the social marginalization and persecution of Alawites.

Secrecy as Survival

Secrecy is not incidental to Alawite tradition; it is foundational. Religious knowledge has historically been disclosed only to initiated men, and even then gradually. This guardedness was not a theological preference, but a response to danger. From the medieval Abbasid period through the long centuries of Ottoman rule, Alawites faced repeated campaigns of repression, heavy taxation, and social ostracism.

The result was a community that learned to conceal its inner life from the outside world. Outward conformity — presenting as generic Muslims — became a strategy of survival. Inwardly, shared rituals and narratives fostered cohesion and resilience. The Alawites endured not by proselytizing or asserting themselves, but by retreating, remembering, and adapting.

Mountain Life

Geography reinforced this social pattern. For generations, Alawites lived in the rugged coastal mountain ranges of western Syria, regions poorly integrated into imperial economies and largely neglected by central authorities. Life there was harsh, agrarian, and communal. Clan ties mattered more than formal hierarchies, and religious authority was diffuse rather than centralized.

This marginal existence further insulated Alawite belief from external influence, but it also entrenched poverty. By the late Ottoman period, Alawites were among the most economically disadvantaged populations in Syria — isolated from cities, education, and political power.

Colonialism and the Reversal of Fortune

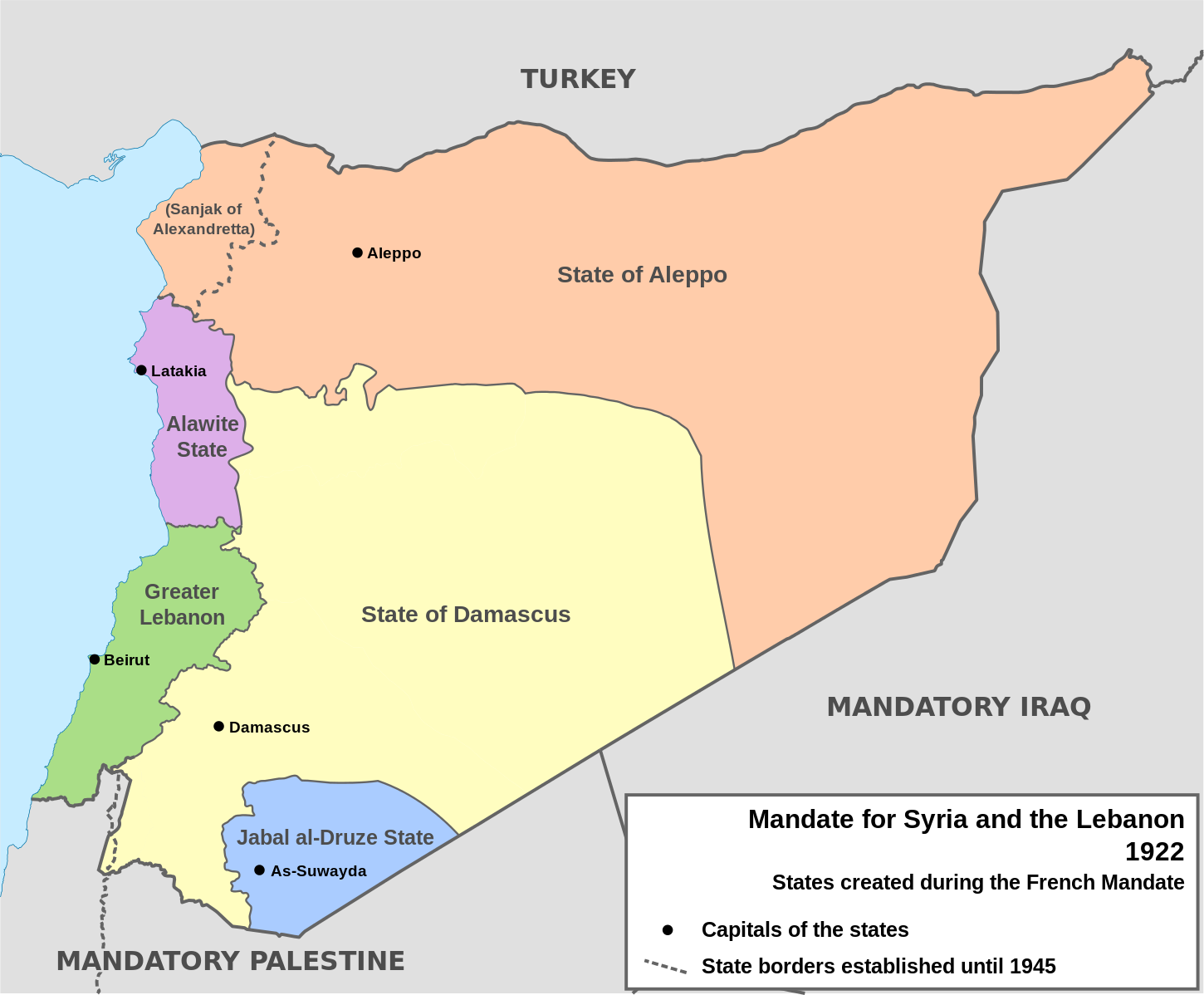

The twentieth century marked a dramatic rupture. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Syria came under French Mandate rule. Pursuing a strategy of divide and rule, French authorities cultivated minority communities as a counterweight to Sunni Arab nationalism. An autonomous Alawite state was briefly established along the coast, and minorities were heavily recruited into colonial military forces.

For many Alawites, military service provided unprecedented access to education, income, and social mobility. This pathway would prove decisive after independence, when the army became a key avenue of political power. Over time, Alawite officers rose through the ranks, culminating in the ascent of Hafez al-Assad, who seized control of the Syrian state in 1970.

Power Without Protection

The association between Alawites and political power is recent — and misleading. While the Assad family and many senior military figures were Alawite, the majority of Alawites remained rural, working-class, and distant from the levers of authority. Yet in the logic of modern sectarianism, collective identity eclipsed social reality.

During the Syrian civil war and recent conflicts, Alawites were widely perceived as synonymous with the regime itself, making entire communities targets of retribution. For many Alawites, this resurrected ancestral fears of annihilation, reinforcing communal solidarity forged through centuries of vulnerability.

Like any society, Alawite communities have contained internal disagreements, dissenting voices, and divergent political choices — realities too often erased when an entire population is flattened into a single narrative of loyalty or blame. Acknowledging the historical formation of Alawite fears does not diminish the suffering of other Syrians, whose losses and traumas during recent decades are no less real and profound.

Yet historical vulnerability does not fully explain how Alawite identity became entangled with the machinery of domination in modern Syria. The rise of Alawite officers within the military and security services did not occur in a vacuum of fear alone, but within a system that rewarded loyalty, silence, and the consolidation of power through kinship and regional networks. For some, especially those who ascended into the officer corps or party-state institutions, survival gradually blurred into privilege, and protection into control. These dynamics fractured Alawite society itself, producing sharp divisions between rural communities that bore the human costs of war and urbanized elites who benefited from proximity to the state. Acknowledging this history does not justify collective punishment, nor does it reduce Alawite identity to regime allegiance; it instead recognizes that communities shaped by exclusion can, under certain conditions, become participants in new hierarchies — even as many of their members remain marginal, fearful, and constrained by choices not of their making.

Faith, Identity, and Public Silence

Today, Alawite identity exists in a delicate balance between visibility and discretion. Publicly, many Alawites emphasize their Islamic credentials, often aligning themselves with Shi’ism. Privately, distinctive beliefs and rituals persist, largely unspoken and carefully guarded.

This duality is not hypocrisy but historical memory. The Alawite experience has taught that survival often depends on knowing what not to say, when not to explain, and how to remain legible enough to belong without revealing too much.

Beyond Regime and Sect

In contemporary debates, the Alawites are often discussed almost exclusively through the lens of power, loyalty, or culpability. That framing obscures more than it reveals. Long before their association with the modern Syrian state, Alawite communities developed under conditions of exclusion, economic marginalization, and religious suspicion, shaping patterns of discretion and inwardness that persist today.

Understanding this history does not require endorsing any political authority. It does, however, require separating a community’s inherited religious and social formation from the actions of states, elites, and armed actors who claim to act in its name.

Seen in this light, the Alawites are neither an ahistorical sect nor a monolithic political bloc, but a population whose past helps explain its worldview. Any genuine attempt to understand Syria — its fractures, its alliances, and its mistrusts — is incomplete without that nuance.