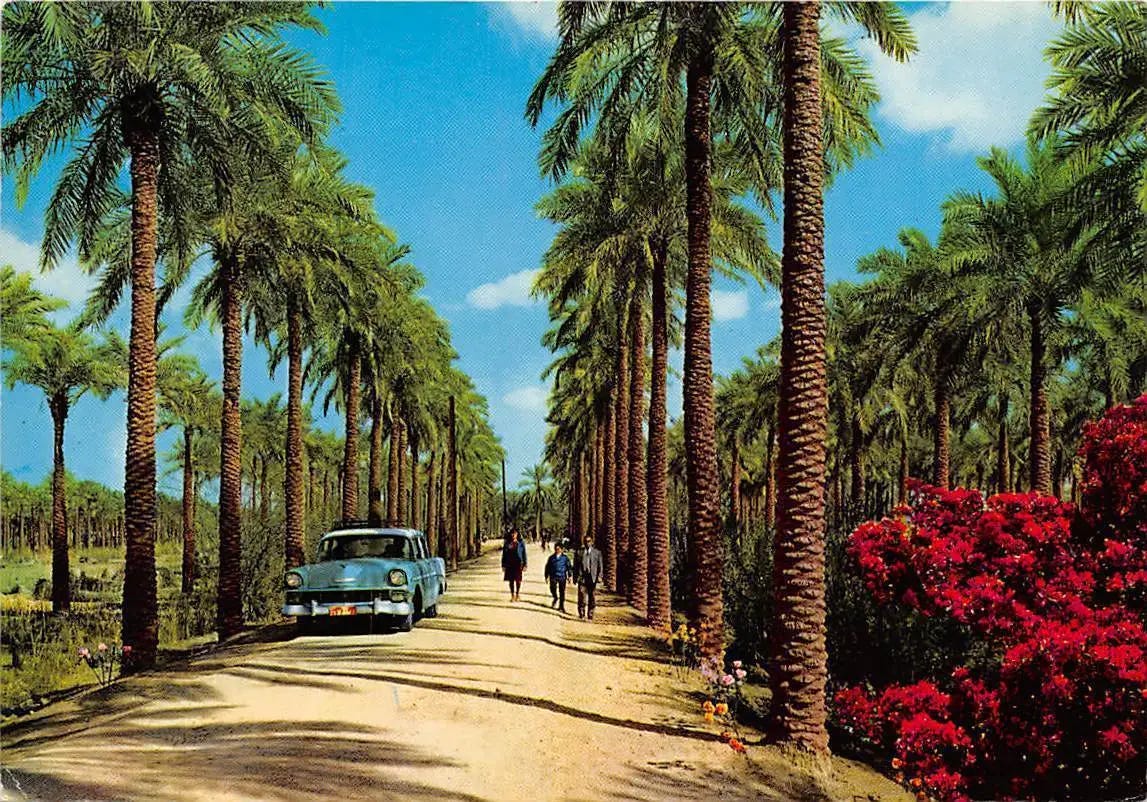

In Iraq, the date palm is not scenery, it is presence. It stands along riverbanks, at the edges of towns, in the background of childhood memories and old photographs. It shades courtyards, feeds families, marks seasons, and absorbs history in silence. To understand Iraq — its patience, its losses, its defiant continuity — one must look up at the tall, feathered crown of Phoenix dactylifera.

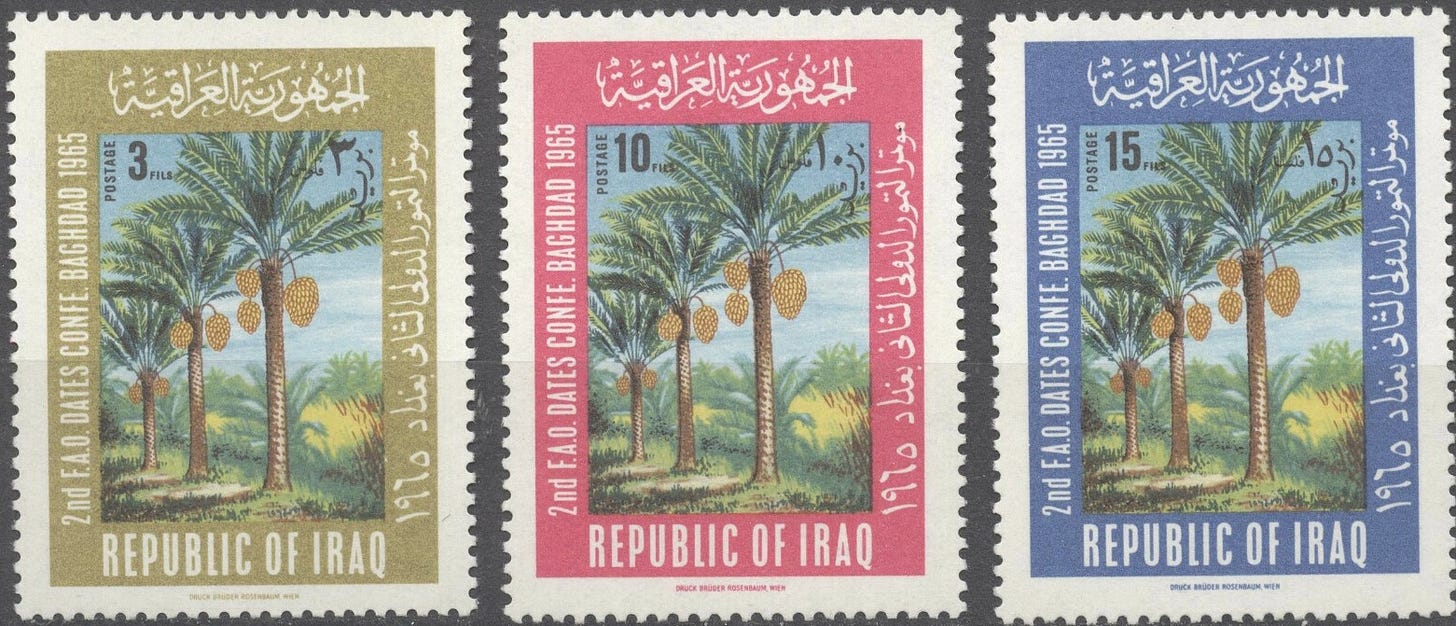

Few places on earth are as deeply intertwined with a single tree. Between the Tigris and Euphrates, the date palm has been cultivated for thousands of years, long before borders, flags, or modern names. Ancient Mesopotamian texts speak of dates not as luxuries but as necessities, carefully categorized and traded. Laws were written to protect palm groves; kings were depicted among them. The palm was never ornamental, it was infrastructure — economic, social, and spiritual.

Its form alone explains part of its power. The date palm grows straight and tall, resisting collapse even in poor soil and punishing heat. Its roots reach deep, finding water where none seems possible. For generations of Iraqis, this endurance became symbolic without needing explanation. The palm did not complain. It survived floods and droughts, invasions and neglect. It gave, year after year.

By the mid-20th century, Iraq was home to one of the largest palm populations in the world, with hundreds of named varieties. Zahdi in the north and center, Khastawi along the Euphrates, Barhi and Halawi farther south — each tied to place, taste, and custom. Dates were eaten fresh or dried, turned into syrup, stored for winter, or offered to guests. Nothing was wasted. Trunks became beams, fronds became mats and baskets, pits fed animals. The palm shaped an entire material culture, modest and ingenious.

But beyond utility, the date palm lived in language and feeling. In Iraqi poetry, it appears as a figure of dignity and sorrow, often standing alone against a burning sky. In religious imagination, it is a blessed tree, associated with generosity, shelter, and sustenance. To offer dates is to offer welcome; to plant a palm is to think beyond one’s own lifetime. Even Iraqis who have never worked a grove speak of palms with intimacy, as if they were relatives left behind.

The devastation of Iraq’s palms over recent decades is therefore not merely environmental or agricultural. It is cultural. War flattened orchards. Salinity crept into the soil as water systems collapsed and river flows changed. Fires, neglect, and displacement took their toll. From tens of millions of palms, Iraq’s groves were reduced dramatically, leaving behind skeletal trunks and abandoned land. The image of the palm — once synonymous with abundance — became an image of grief.

Yet the palm remains. It reappears wherever water returns, wherever someone decides to stay. In recent years, quiet efforts to revive palm cultivation have been taking place across Iraq. Farmers are replanting, researchers are cataloguing endangered varieties and families are returning to land that had been written off. These acts matter. A palm does not grow quickly. To plant one is to believe, stubbornly, in a future that may not immediately reward you.

For readers across the Arab world, Iraq’s palms feel familiar. The region understands trees as more than plants: cedars in Lebanon, olives in Palestine, figs and citrus along the Mediterranean. These are not just crops; they are memory anchors. The Iraqi date palm belongs to this shared emotional geography. Its suffering mirrors broader regional wounds, and its survival carries a collective hope.

Phoenix dactylifera teaches a particular lesson, one that modern life often resists. It asks for patience. It demands care over decades, not quarters or election cycles. It reminds us that heritage is alive — or it disappears. You cannot archive a palm tree in a museum and expect it to mean bloom. It must be watered, protected, allowed to grow tall enough to feed and cast shade for others.