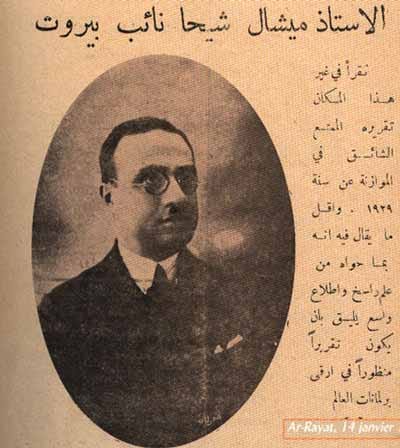

Michel Chiha’s intellectual and political sensibility was shaped long before the birth of the Lebanese state. Banker, essayist, and political thinker, he would later become one of the principal intellectual architects of Lebanon’s constitutional and economic frameworks.

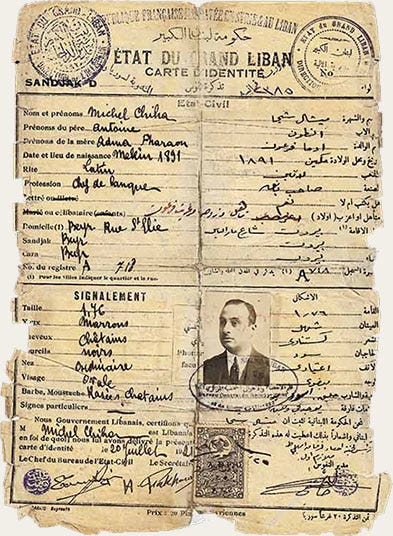

Born in Bmekkine on September 8, 1891, he belonged to a Greek Catholic family whose prominence within the Antiochene Church extended back to the eighteenth century.

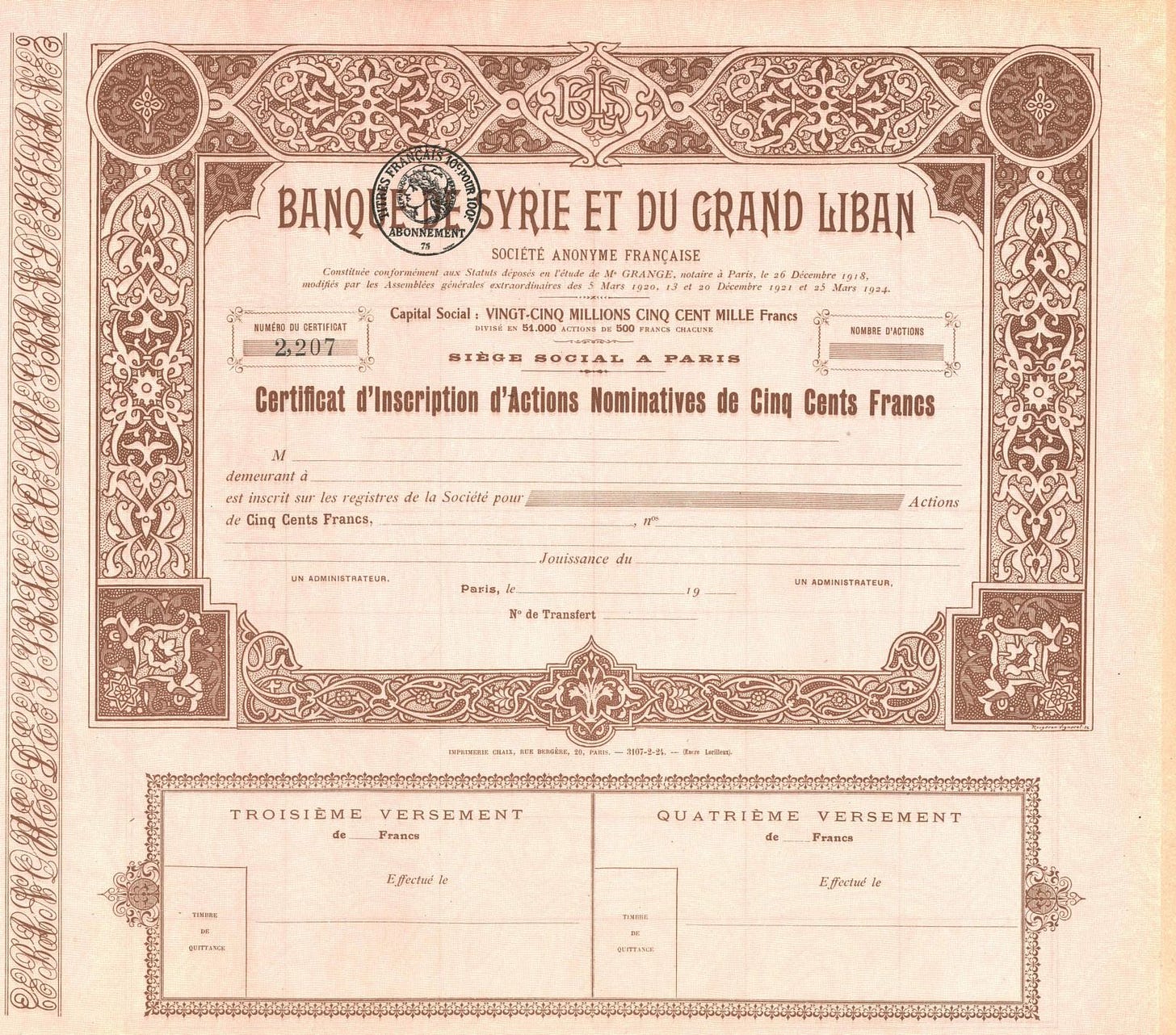

He was the long-awaited son after six daughters. His father, Antoine Chiha, co-founder of the Pharaon and Chiha Bank in 1876, died in 1903, leaving behind a financial institution that embodied commerce, continuity, and international engagement. For Michel Chiha, inheritance was never just material, it was moral and intellectual as well — a transmission of habits, standards, and obligations that he would later reference throughout his life.

Commerce and Memory

Chiha’s evocation of his forebears offers a revealing portrait of the world that formed him. Writing in 1942, he recalled his father and grandfather moving confidently through global networks of trade — selling silk, buying coal, receiving gold and letters of credit — animated by a love of life as much as by commerce (Chiha, “Le vieux passage,” Le Jour, December 25, 1942). These men were neither adventurers nor ideologues, but traders in a classical sense: prudent, worldly, and anchored in reputation.

This environment fostered in Chiha an early understanding of confidence as a social currency. Trade depended not on force but on credibility, on the accumulation of trust across borders, confessions, and cultures. This lesson would later migrate from the realm of banking into Chiha’s conception of politics, where confidence — between communities and institutions — would become a central principle.

Education and Temperament

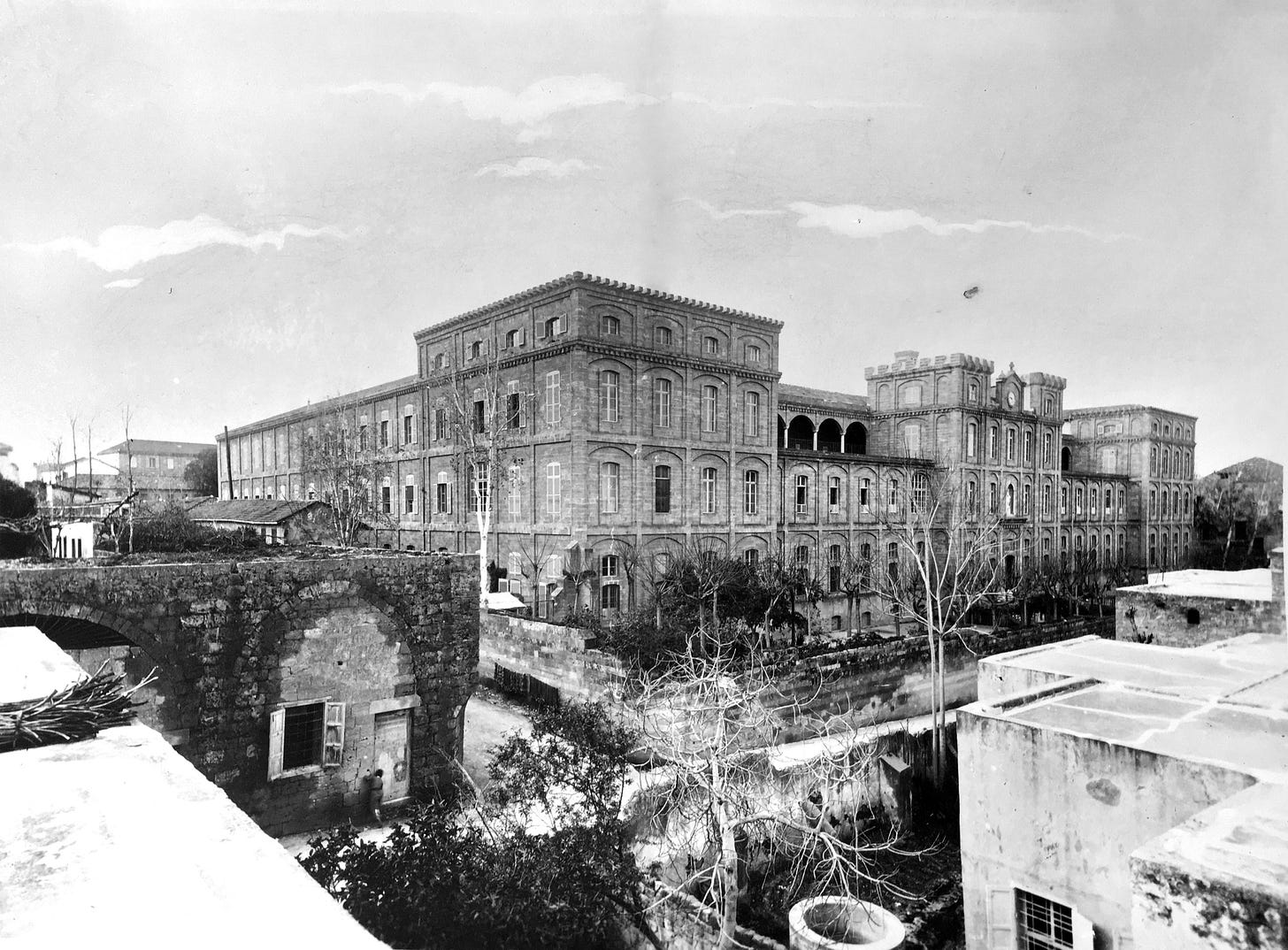

Chiha received his formal education at the Jesuit Université Saint-Joseph in Beirut, graduating in 1906. His intellectual formation, however, was shaped as much by travel as by study. Of delicate health, he accompanied his mother on frequent journeys to Europe and spent extended periods in England, particularly in Manchester, where he lived with an uncle.

These early experiences introduced him to a culture markedly different from the French intellectual tradition in which he was otherwise steeped. Chiha developed a lasting admiration for English pragmatism, and skepticism toward abstraction. Looking back decades later, he recalled his student years not with nostalgia but with a sense of continuity, emphasizing moderation, temperament, and proportion (Chiha, “À propos d’un sujet de concours,” Le Jour, June 14, 1946).

At sixteen, he entered the family bank after gaining experience in an English commercial firm. Commerce, for Chiha, was not an impediment to intellectual life, it was a school of realism — one that trained judgment and discouraged illusion.

Exile and Awakening

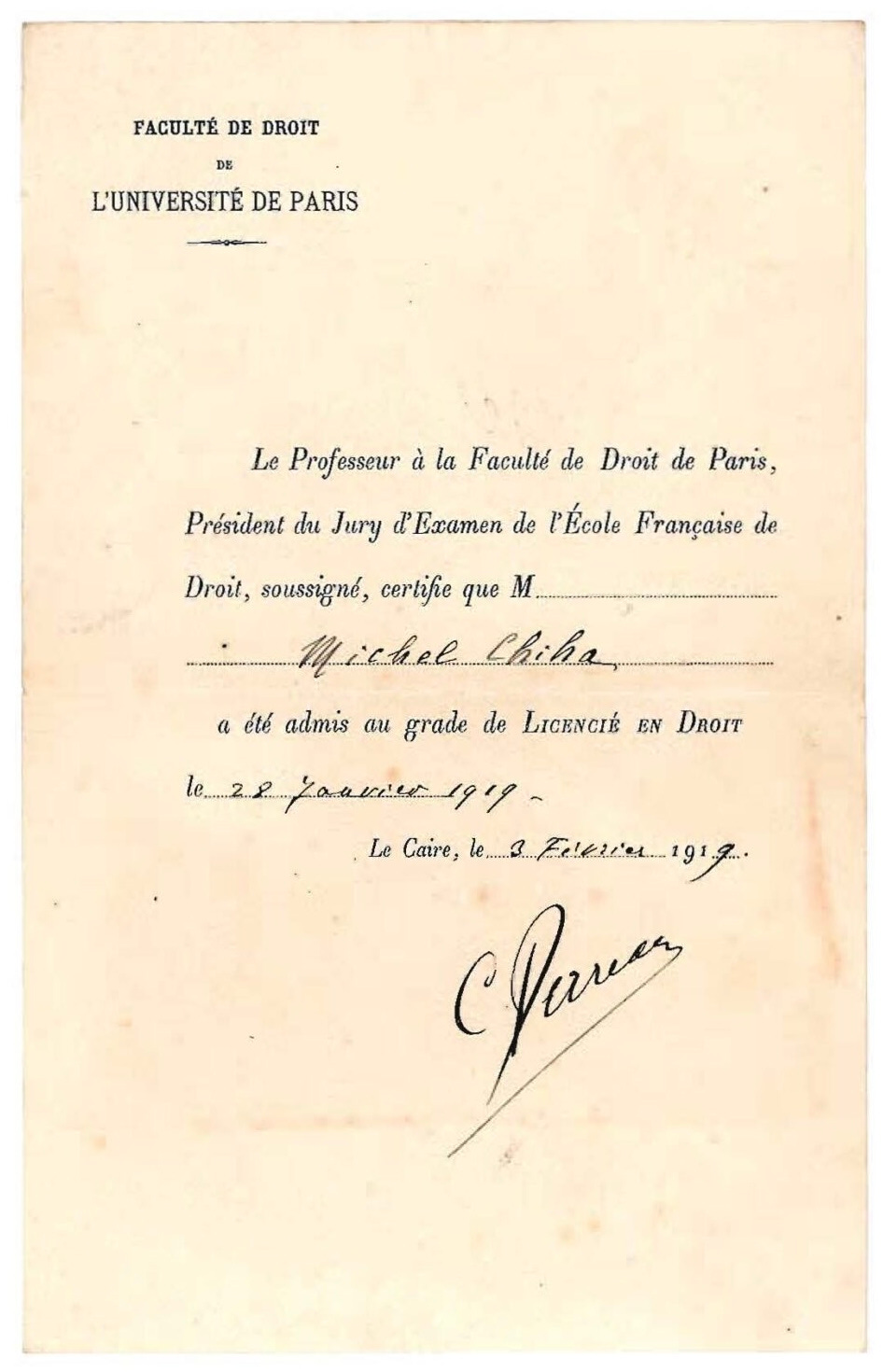

The First World War interrupted this early trajectory. Like many Lebanese, Chiha went into exile to escape Ottoman repression between 1914 and 1918, settling in Egypt. Cairo, Helouan, Alexandria, and Ras-el-Bar became the geography of his formative displacement.

During these years, Chiha studied law and obtained his degree, while immersing himself in the cultural and political life of the Levantine diaspora. Anticipating the defeat of the Ottoman Empire and the reconfiguration of the region, he joined a small group of similarly minded intellectuals, such as Charles Corm and Petro Trad, and determined to prepare the intellectual groundwork for a future Lebanese state.

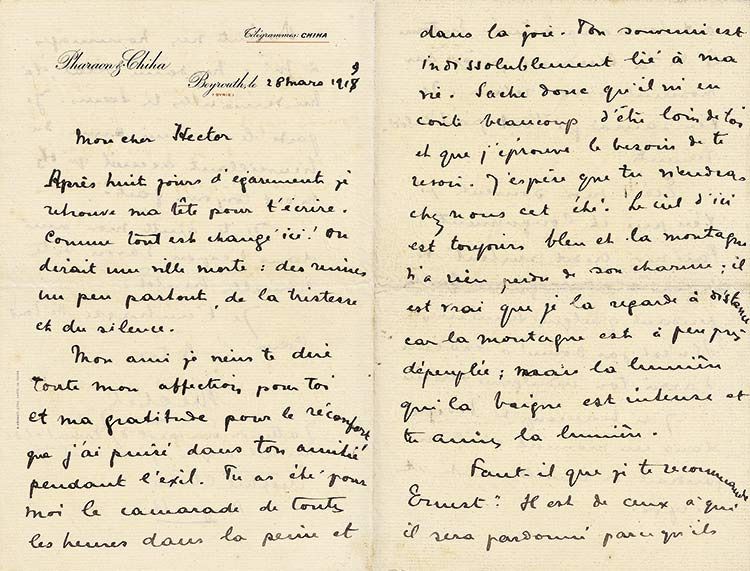

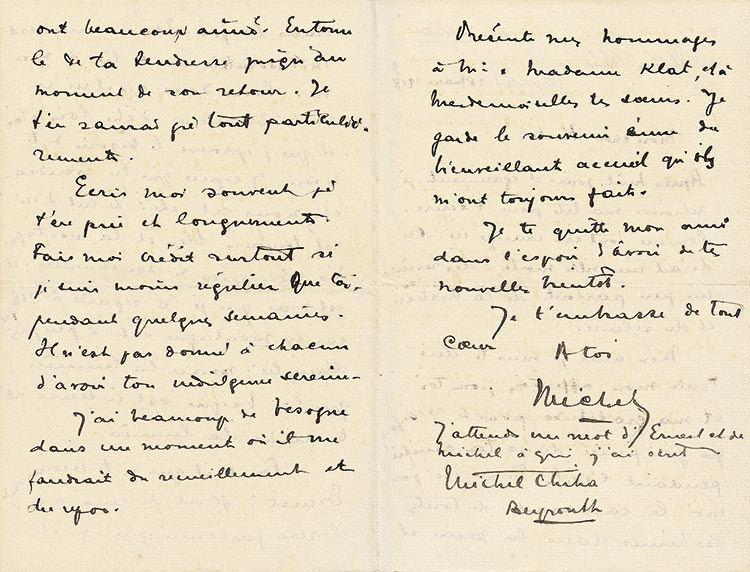

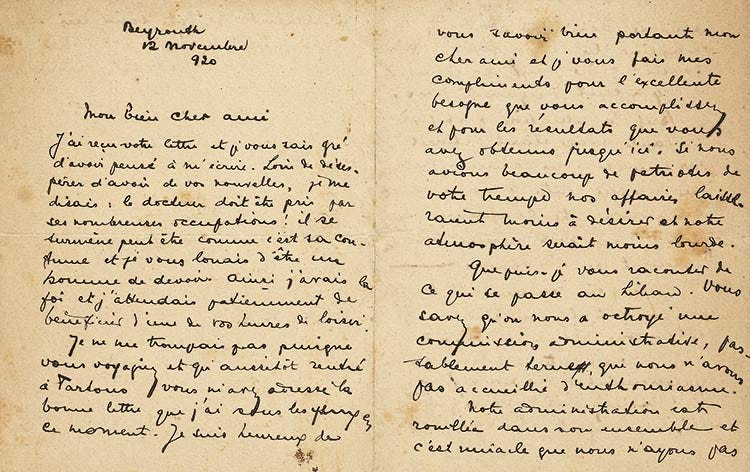

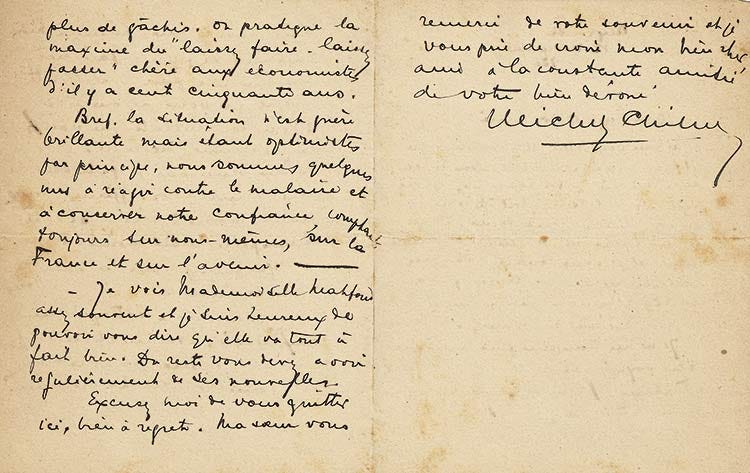

One of their efforts culminated in Ébauches, a French-language journal defined by its non-partisan ethos and its deliberate refusal of dogma. Its motto — “take me as you find me” — captured Chiha’s instinctive mistrust of ideological rigidity (Chiha, letter to Hector Khlat, wartime correspondence). Politics, he believed even then, had to remain provisional, attentive to circumstance rather than abstract principle.

Exile also deepened Chiha’s cultural pursuits. His correspondence reveals sustained engagement with music, literature, archaeology, and art. These interests were not ornamental, they reflected a belief that civilization could not be reduced to politics alone, and that cultural continuity was as vital to nation-building as institutional design.

Return to Ruins

Chiha returned to Beirut in 1919 to a country devastated by famine and war. Nearly a quarter of the population had perished, and much of the built environment lay in ruins. Writing shortly after his return, he contributed to La Revue Phénicienne which was established by Charles Corm in Beirut. In this period, he described Beirut as “a ghost town; ruins, sadness, and silence everywhere” (Chiha, letter to Hector Khlat, Beirut, March 28, 1919).

Despite exhaustion and disillusionment, Chiha assumed responsibility for the Pharaon and Chiha Bank at one of the most difficult moments in Lebanon’s history. Economic reconstruction, he understood, was inseparable from political stabilization. Credit, confidence, and institutional reliability were not secondary concerns; they were foundational.

His personal letters from this period reveal a sober appraisal of public life. Writing in 1920, he lamented the stagnation of administration and the mechanical invocation of laissez-faire principles, while affirming a cautious optimism grounded in effort and responsibility: “being optimists by principle, we are a few to react against the malaise and to keep our confidence” (Chiha, letter to Dr. Mahfoud, Beirut, November 12, 1920). This combination of critique and restraint would become characteristic of his public interventions.

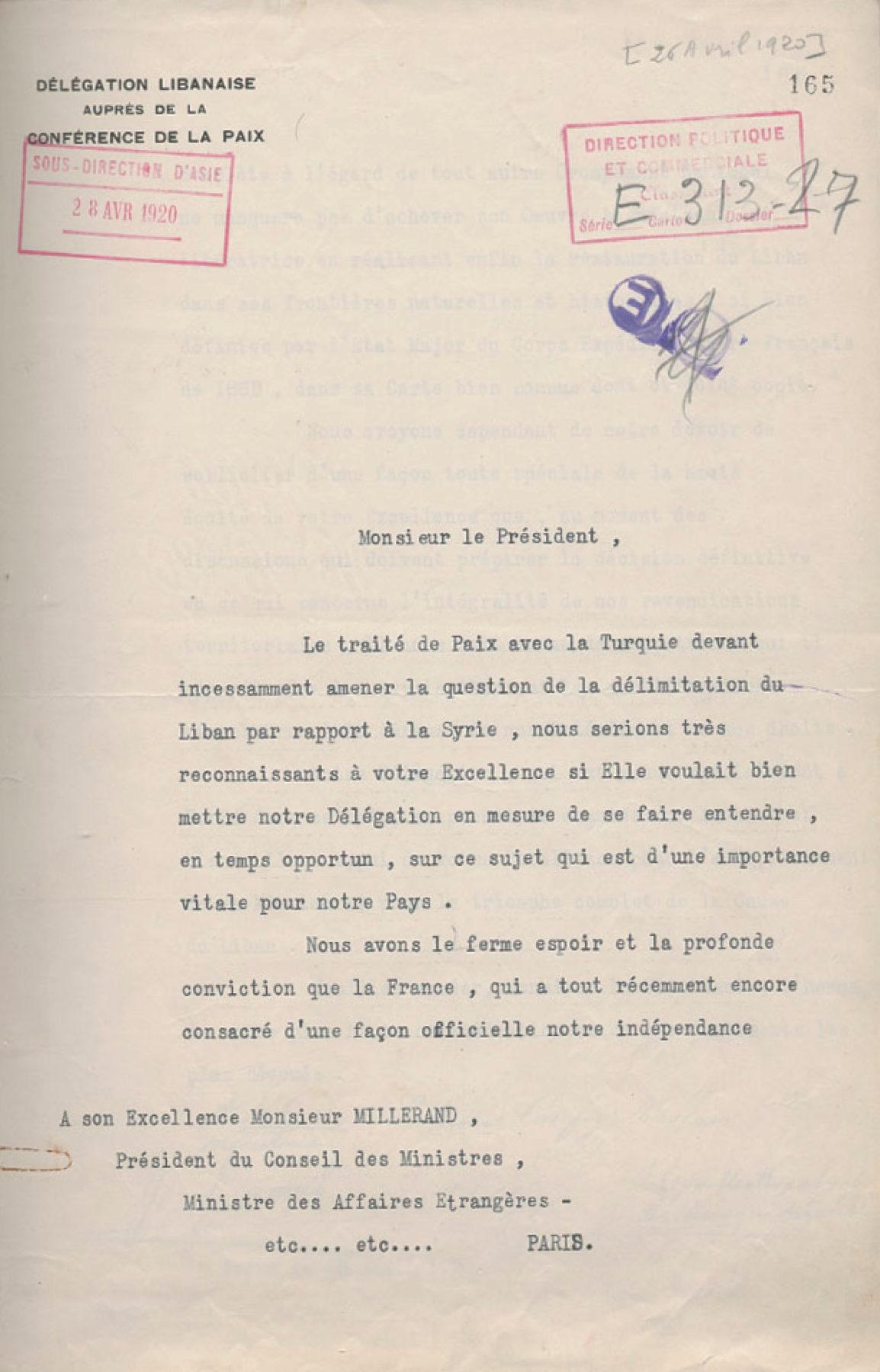

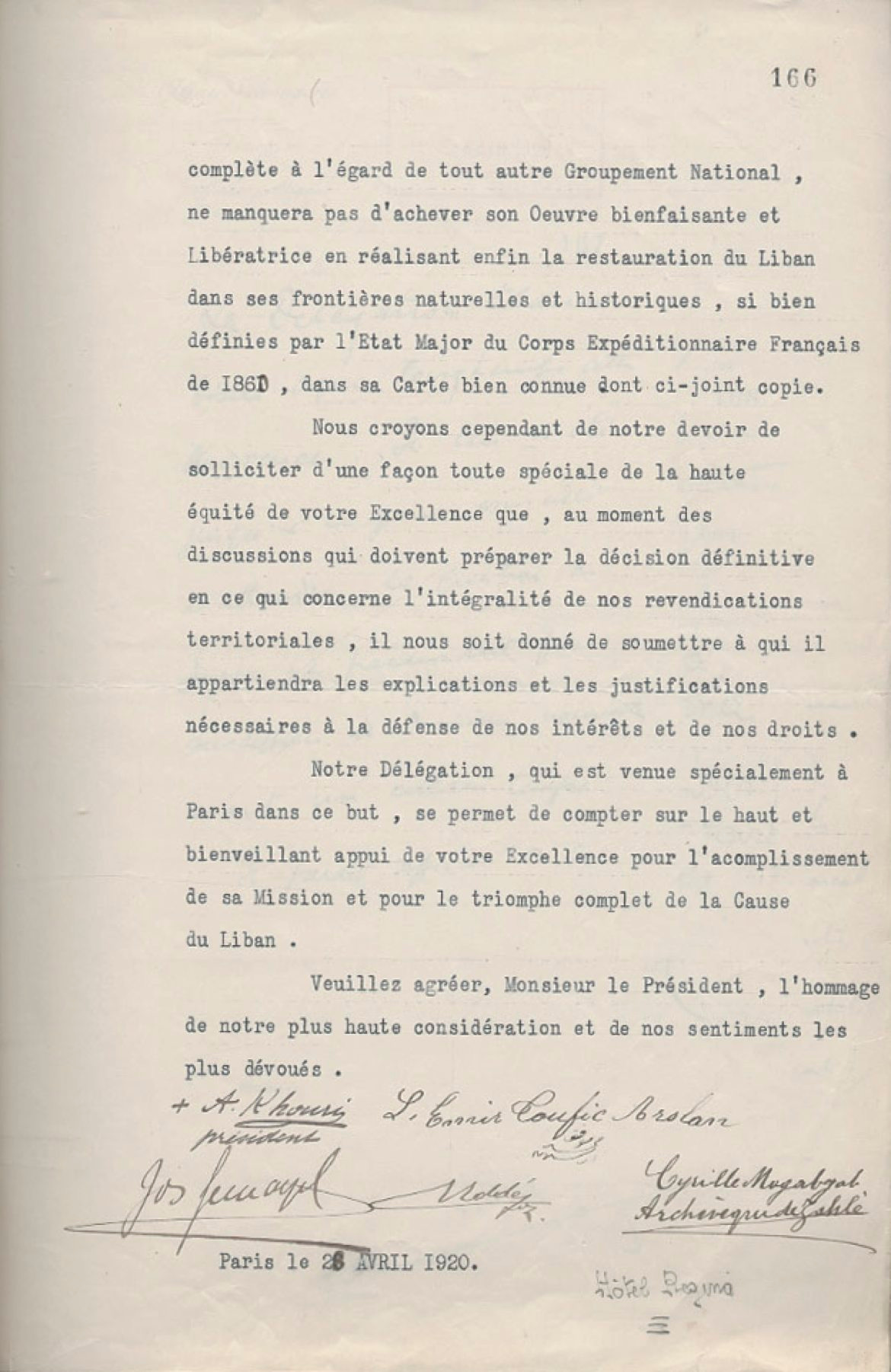

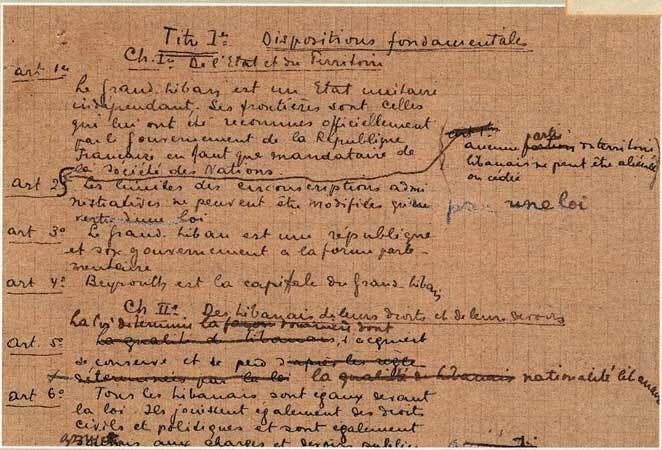

Greater Lebanon

The proclamation of Greater Lebanon on September 1, 1920, following the Treaty of Versailles, marked a decisive moment. For Chiha, this was neither a romantic culmination nor an abstract fulfillment of nationalist aspiration. Statehood was a fragile construction — one that required careful calibration between geography, demography, economy, and culture.

Chiha did not conceive Lebanon as a homogeneous nation modeled on European precedents. His formative experiences — family mediation, exile, commerce, and cultural plurality — had taught him that Lebanon could exist only as a negotiated entity. Diversity was not an obstacle to be erased but a condition to be managed through balance, guarantees, and restraint.

In the years that followed, Chiha would play a central role in shaping the intellectual framework of the Lebanese state.

His innate reluctance to engage in active politics was reflected in the long hesitation before he finally declared himself a candidate for the minority seat. Although he eventually agreed to stand — largely due to pressure from his friends Omar Beyhum and Omar Daouk, who were eager to include him on their joint electoral list — he was deeply appalled by the unscrupulous tactics commonly employed during election campaigns. At one point, his revulsion was so strong that he nearly withdrew his candidacy midway through the election. Only a sense of loyalty to his fellow candidates kept him from stepping aside altogether.

Despite eventually being elected in 1925 as a Deputy of Beirut for religious minorities in parliament, his contribution to nation-building lay less in political office than in constitutional sensibility: the insistence that power be limited, authority dispersed, and coexistence institutionalized rather than assumed.

Banking on the Ethics of Trust

Chiha’s reflections on banking illuminate his broader political philosophy. He helped establish the Beirut Stock Exchange in 1941 and, in a 1945 essay, he rejected prevailing caricatures of financiers as either plutocrats or mere technicians. Banking, he argued, originated as an act of common faith. A banker was above all a man of credence — one entrusted with collective confidence (Chiha, “Carrières,” La Revue des Deux Mondes, 1945).

This conception extended beyond finance. Trust, once broken, was difficult to restore; authority, once abused, lost legitimacy. For Chiha, the same principles governed pluralistic societies. Political systems, like financial ones, depended on credibility, restraint, and the careful management of risk.

It was this logic that underpinned his approach to Lebanon’s institutional architecture. Confessional balance, economic liberalism, and limited state power were not ideological commitments but practical safeguards — mechanisms designed with the intent to prevent domination and reassure communities in a volatile regional environment.

Fragile Conditions

Michel Chiha’s nation-building project was neither utopian nor meant to be static. It assumed fragility as a permanent condition. Lebanon, he believed, could survive only as a country of moderation and a carefully negotiated coexistence.

This vision has often been criticized for entrenching sectarianism or privileging economic elites — such critiques cannot be dismissed. Yet they overlook the historical wager at the heart of Chiha’s thought: that in a deeply plural society, stability could not be imposed by force or ideology, but only cultivated through confidence, restraint and equitable representation.

Chiha did not seek to invent a new society. He sought to preserve an existing one by giving it institutional form. His contribution to modern Lebanon lay precisely in this effort to translate lived plurality into political structure, but the political ethos of his time wasn’t so different:

“It’s always the same old story. In Lebanon political concessions usually mean rushing backwards into self-protecting policies. What poor thinking! A strong President would follow the Constitution and not seek re-election…Lebanon’s best hopes lie not in the might of an individual but in that individual’s integrity.”

Michel Chiha told Le Jour on July 24th, 1952. The attainment of Independence in 1943 and the election of his brother-in-law Béchara El Khoury as President of the Republic, established Chiha as the Administration’s main advisor, a role which he would fulfil until May 1949 when Khoury decided to extend his presidential mandate for a further six years, against Chiha’s will.

Michel Chiha never saw Lebanon’s fragility as failure. He understood its pluralism, volatility, and vulnerability to regional forces as structural, not temporary flaws. However, he didn’t anticipate how these conditions would evolve once power left the hands of those he trusted to manage it.

Confidence; Betrayed and Misjudged

Chiha passed away in 1954, and over seventy years later, Lebanon’s tragedy lies not in its peculiarities, but in how they were exploited and hollowed out. The trust his system relied on — between communities, institutions, and the economy — was squandered.

Chiha’s vision wasn’t just betrayed; it may have also been misjudged despite his best intentions. He was right about much: Geography mattered, some form of power-sharing was inevitable, and pluralism couldn’t be denied without catastrophic cost.

But Chiha overestimated the integrity of elites, imagining that communal leaders would act as guardians, not self-serving opportunists. He created institutions that were inherited by warlords and political machines. He also treated sects as stable, ignoring class divisions and social change. By embedding sectarianism in state institutions, he transformed it into a permanent organizing force, incentivizing, rather than containing, sectarianism.

His faith in economic interdependence proved to be equally misplaced. Economic growth was uneven, and when the economy stalled, the absence of strong social welfare institutions left citizens relying on sectarian structures for protection.

Chiha’s vision of neutrality also rested on unrealized conditions — regional restraint and external guarantees Lebanon never had. In a region driven by hard power, Lebanon’s openness invited external intervention and conflict.

The question is: Was Chiha’s approach inevitable? Almost certainly, but not entirely.

Lebanon emerged from imperial design and communal bargaining, not revolution. In this context, Chiha’s pluralism was defensive realism, not idealism. However, where inevitability ends, choice begins. Pluralism may have been unavoidable, but its institutional entrenchment wasn’t. Chiha prioritized stability over evolution, and what should have been temporary became permanent. Time, which he thought would soften identities, only hardened them.

Ironically, his system worked just enough to delay reform — stabilizing without transforming, reassuring without integrating. When collapse came, it was total. But it wouldn’t be fair to blame him entirely for that; rather, his system was as a starting point which should have evolved.

Chiha’s legacy is vital — not necessarily as a model to restore, but as a warning which was heeded too briefly and trusted for too long.

As parliamentary elections approach, the question is no longer what Lebanon’s leaders promise — as they have long spent that currency — but what its voters continue to reward. In Thomas Jefferson’s words, “the government you elect is the government you deserve.”

Lebanon will recover not through empty promises, but when confidence is reclaimed from those who trade it for themselves.