Kenneth Khouri — A Lebanese Jamaican Pioneer Who Captured a Nation’s Sound

By Ralph I. Hage, Editor

History often begins without anyone noticing. Sometimes it begins with a broken radio, a chance conversation, and a man curious enough to listen.

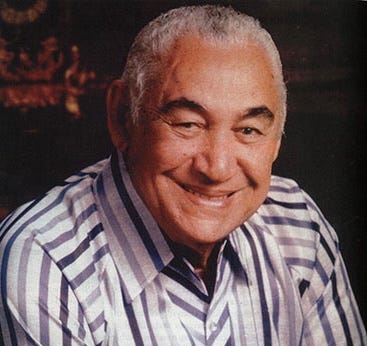

When Kenneth Khouri bought a disc-recording machine in Miami in the late 1940s — almost on a whim — he did not imagine that the decision would alter the cultural destiny of Jamaica. Yet from that accidental purchase emerged the island’s first recording studio, its first pressing plant, and the industrial foundations of ska, rocksteady, and reggae. Long before Jamaican music conquered the world, it had to be pressed somewhere. It had to be believed in. Khouri was the one who did both.

Born in 1917 in St. Mary, Jamaica, and raised between rural Highgate and Kingston, Khouri was the child of layered migrations. His father arrived from Lebanon at the age of twelve, fleeing war with his parents, and would remain in Jamaica for most of his life, returning only once, at seventy-one. His mother was Jamaican-born of Cuban descent. Khouri himself rarely romanticized these journeys, but he understood them instinctively.

“They were running away from the wars, I guess… this is just where they ended up.”

Kenneth Khouri as told to David Katz

That phrase — this is just where they ended up — could serve as a thesis for much of the Lebanese diaspora in the Caribbean. It also frames Khouri’s own life, shaped less by grand design than by decisive responses to circumstance.

As a young man, Khouri worked in his father’s dry goods and furniture businesses in Kingston, and later with Joseph Issa, part of the Lebanese-Syrian commercial networks that underpinned much of Jamaica’s retail economy. Issa’s company distributed jukeboxes across the island, exposing Khouri to popular music not just as abstraction, but as circulation — sound moving through space, shops, bars, and bodies.

“I didn’t like the furniture business. I was born musically inclined.”

That inclination found its opening when Khouri traveled to Miami to seek medical treatment for his father. While there, he overheard a conversation about a disc-recording machine. He bought it, along with a hundred blank discs, for $350. An instinctive purchase. As soon as he returned, he began recording voices on the machine.

“People were so fascinated with it, I couldn’t find enough time to do them.”

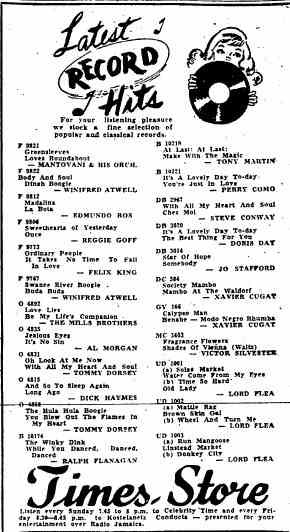

Back in Kingston, Khouri built his first studio. It was a small wooden building with a zinc roof, where recordings were mainly done at night to avoid the daily noise of the traffic. He began recording voices, then calypso performances in nightclubs. He mailed his discs to Decca Records in London, asking if they could be pressed. They said yes. The first song he recorded — Lord Flea’s “Naughty Little Flea (Where Did the Little Flea Go)” — became a modest hit and a milestone: the dawn of Jamaica’s modern recording industry.

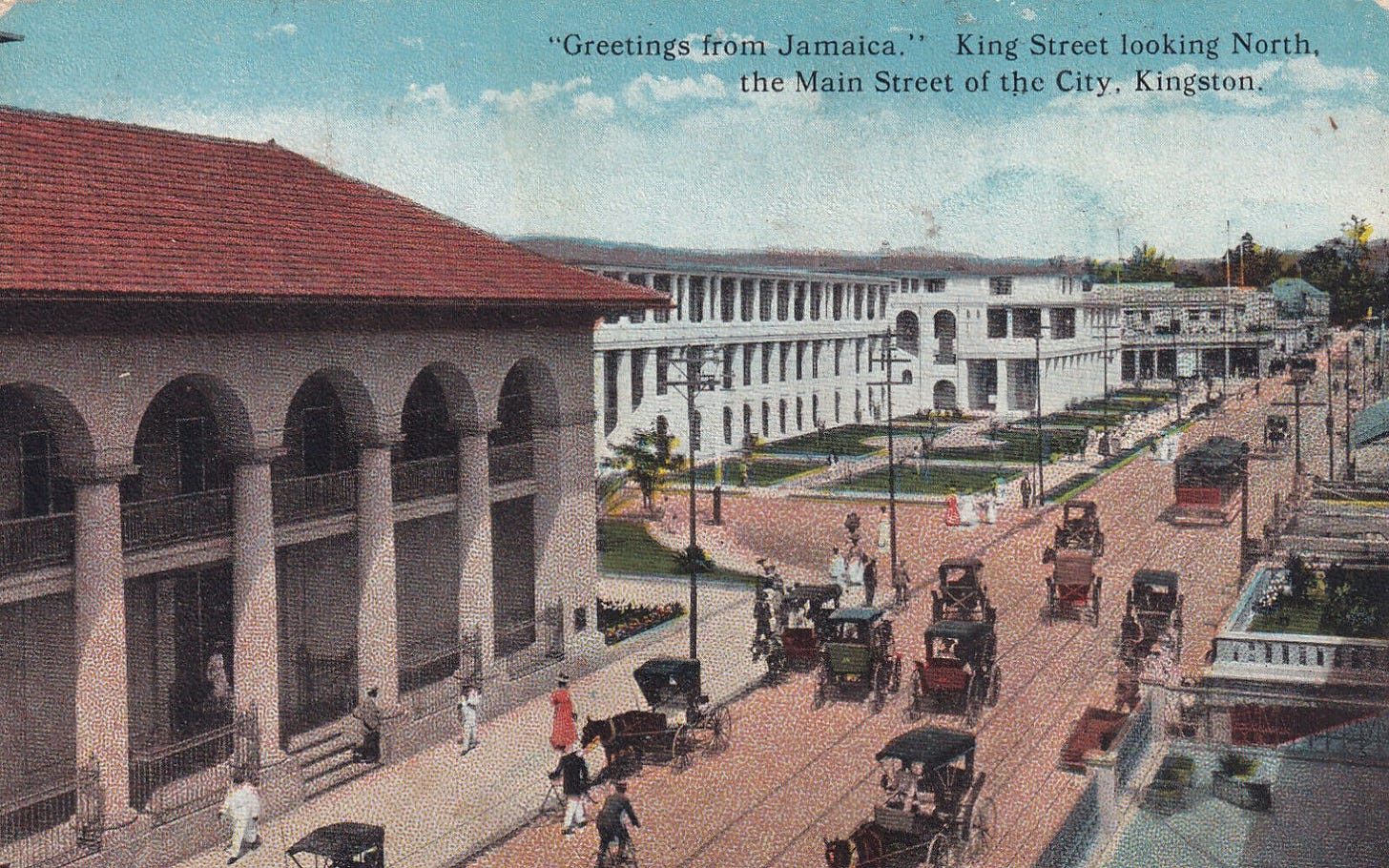

By 1947, working out of 129 King Street with his wife Gloria, Khouri had built the island’s first true recording studio, Records Limited. One microphone. One track. No precedent.

“Nobody else had recording facilities in Jamaica at that time… so I am the complete pioneer of everything.”

For the first time, Jamaicans could hear their own voices played back through machines — unchanged, unfiltered, and unmistakably their own. In partnership with Alec Durie of Times Variety Store in Downtown Kingston, Khouri launched Times Records, whose calypso releases sold out quickly.

Unsatisfied with relying on overseas pressing, he traveled to California, acquired record-manufacturing equipment — and after an initial learning curve — taught himself the trade. Jamaica’s first pressing plant followed.

Khouri was part of a small group of early industry builders — including Stanley Motta of Motta’s Recording Studio — who helped ensure Jamaican music could be recorded, preserved, and circulated locally.

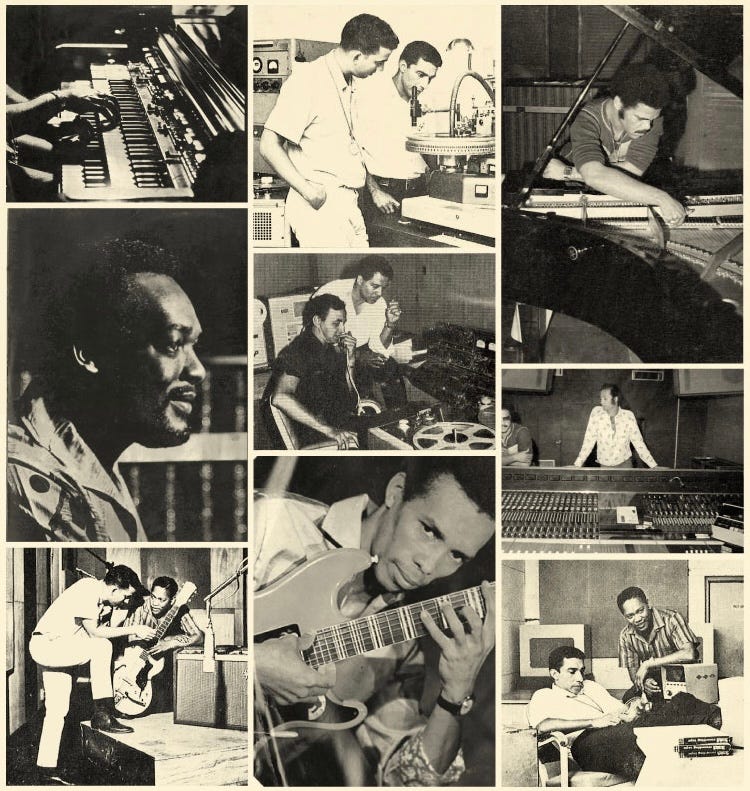

By the mid-1950s, Khouri was producing mento, jazz, and international releases under franchise agreements with American labels like Mercury. In 1957, he relocated operations to Marcus Garvey Drive, founding Federal Records and transforming Records Limited into its subsidiary. Federal would become the beating industrial heart of Jamaican music. Artists and producers gravitated toward him because there was nowhere else to go.

“Everybody that was in the record business passed through my hands.”

Among those who passed through were Prince Buster, Hopeton Lewis, Clement “Coxsone” Dodd, Duke Reid, and a young Chris Blackwell — who once asked Khouri to help launch Island Records in London. Khouri declined, choosing Jamaica over the metropole despite allowing Island to use Federal Records as the hub for early Island Records productions. His studio became a crucible where ska hardened into rocksteady, and rocksteady gestured toward reggae.

When a fire damaged part of Federal in the 1960s, Khouri rebuilt — this time as a world-class studio that drew international artists, including Paul Anka. Federal Records released hit after hit, embedding Jamaican sound into global circulation.

The 1970s brought political violence, illness, and eventual migration to the United States. In 1981, Khouri sold Federal Records to Rita Marley, Bob Marley’s wife, who renamed it Tuff Gong. It was an ending, but also a confirmation: the infrastructure Khouri built was strong enough to be inherited.

Kenneth Khouri’s son, Paul, explained in 2003 that his father began recording mento musicians who were performing in hotels, motivated not by financial gain or recognition, but by a genuine interest in music.

Paul also mentioned that even in his old age, his father continued to enjoy playing his records loudly, testing the limits of his mother’s patience. Kenneth often joked that music was his first love, and that his wife of 67 years came second. He passed away at the age of 87 and his sons continued aspects of the business abroad, while his imprint remained indelible at home.

Shortly before his death, Kenneth Khouri was awarded Jamaica’s Silver Musgrave Medal — an honor that, while significant, understated the scale of his contribution.

In Jamaica, he created the conditions for a nation to hear itself: pressing sound into permanence before it dissipated into the air.

▶ Hear a 1960 recording by the Federal Singers, written and composed by Kenneth Khouri: “You’d Better Marry Me”