Lebanese music is often framed through familiar binaries: traditional and modern, Eastern and Western, popular and experimental. While useful, these categories tend to flatten a more complex artistic reality, obscuring a lineage of musicians whose work resists such distinctions altogether.

Ferkat Al Ard is one such example — a Lebanese ensemble that occupies a rare cultural space, neither conciliatory nor oppositional. Their music does not seek to reconcile East and West, but allows them to coexist, unforced, within the same sonic landscape.

مطر الصباح، أخرجني

من جديد

لأسلم على، شوارع المدينة

و حفنة من الرمال

في قلبي

لم أكن أكيداً من دربي

عندما كان المطر المبكر

يوقظ في الشوارع النائمة

سجناء المدينة

و لكن مطر الفجر المقبل

سيكون غزيراً

وسيجرف الرمال عن قلبي

وكل الطوابق العليا

وكل آثام المدينة

وكل آثام المدينة

وكل آثام المدينة

كلمات و الحان: عصام الحاج علي

The music unfolds with layered restraint: choral backing voices that lift rather than embellish, a measured saxophone solo by Toufic Farroukh, and, finally, a piano passage by Ziad Rahbani that brings the piece into sharp focus. What emerges is something moving — recognizably Lebanese, yet unlike anything typically associated with Lebanese music.

The impression lingers. What initially feels unfamiliar gradually reveals itself as quietly assured, even complete. This was not an imitation of Western forms, nor a hybrid designed for easy classification. Rather, it was an autonomous musical statement — drawing from both Eastern and Western traditions without subordinating itself to either, and in doing so, articulating a form all its own.

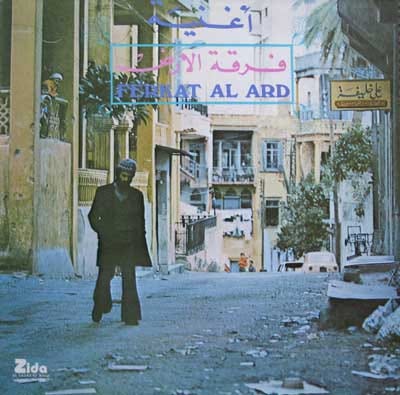

Ferkat Al Ard was formed in the late 1970s around three core members: Issam Hajali, Toufic Farroukh, and Elia Saba. The group released their album Oghneya on cassette in 1978, and later, a vinyl re-issue in 1979. Owing to the financial and material constraints of the civil war, only a small number of copies were pressed. The album has since become a rare and highly sought-after recording.

Years later, I had the opportunity to meet Issam Hajali, who reflected on the formation of the band and the circumstances that shaped it.

How did you know you wanted to be a musician?

You know, I can’t tell you. I really don’t know how I ended up being a musician. I remember when I was eighteen, my father had a hard time accepting it; so he asked me to choose between staying at home or being a musician – I chose to be a musician. It was a big choice – but we later became great friends again when he saw that my musical career had taken off.

In the beginning it was hard. I had pressed my own cassettes for a Ferkat Al Ard early release called Muwasalat Ila Jisr Al Ard and used to try selling one or two a day just to get by. Now a record or cassette for Ferkat Al Ard sells for thousands! Other than those cassettes, I really never made any money from music.

Can you tell me about your beginnings of Ferkat Al Ard?

Well, it was hard to make music at that time. We had to compromise a lot. If a song didn’t include sounds of shooting and bombs, people weren’t interested in buying or relating to it.

I’ve listened to Oghneya and found that it really is hard to categorize. It contains some really avant-garde moments.

Yes, well, again, we really had to make lots of compromises for it to go through with the producers. It is very hard to categorize it – it touches upon many genres and influences. I remember listening to Year of the Cat by Al Stewart, a beautiful song with so many different instrumental solos and every single one was significant – I appreciated that. For example in Matar Al Sabah, people were telling us that when we stopped singing there was no need for music anymore – it was then that I always tried to prove them wrong. So we kept the background singers, saxophone, and piano solo. Entazerni, for example, is a disco track with a heavy-political theme. I don’t know how that one turned out disco – maybe it was the popular sound at the time – but it turned out nice. There’s one track called, Lahnon Lamra’ati Wa Biladi which contains a four minute jam session followed by a brief piano and vocal piece. I was sure the producers wouldn’t understand it, so when we were showing them the final cuts for the album, I fast forwarded through that part! They asked, “What’s that?” I told them, “nothing to worry about!”

The album contains some of the most famous Arab poetry of the 1970s. On which basis did you choose them?

Yes, well, that’s as much as we knew at the time. People like Mahmoud Darwiche and Samih Qasimwere celebrities in the art world and we admired their poetry, and being in the midst of a highly politicized war, we felt we had to address these political issues.

What about Ziad Rahbani?

Ziad… I met Ziad in a small pub – which doesn’t exist anymore – at the end of Hamra next to the current Commodore Hotel called Pizza e Vino. I used to frequent the pub with friends, it was a nice place with an acoustic piano and a bustling music scene. There, I met a Brazilian guy who opened up my musical horizons, he really taught me a few things that stayed with me – I was introduced to Bossa Nova and new guitar techniques in depth – and Ziad and I connected on that level. Plus we were mixing Western and Eastern types of music – which was a completely fresh and special approach at the time – but people weren’t ready to accept it yet. So the band and I showed our music to Ziad and he liked the idea. So we went straight to the studio. He was really great to work with, always trying out new possibilities, and wrote the string arrangements. It was a great experience – he always does things his way, in a great way.

The album has a well-known cover amongst record collectors – what’s the story behind that?

The cover was taken on the street where the band and I were living at the time – in an area next to Wetwat. Actually, you know, the house is still there. In fact, Ziad was also living there at the time and his house shows on the left – where the elevated balcony is. Joseph Sakr lived on the floor above him so we were all neighbors for about a year! Yeah, the cover is about how Ziad saw me – so he asked me to wear a hat and long coat and walk down the street alone.

Did Ferkat Al Ard tour?

Well, we toured and did a few great concerts. We toured a lot in Lebanon – we believed in our musical cause. We did a great concert in West Hall [at AUB]. In fact – we were doing a version of Matar Al Sabah and thought the recording device was on, it turned out it wasn’t and it cut mid-way! Shame, I think it was an even better version than the studio version. We also went to Cuba, Algeria – lots of places. We were very idealistic and believed in our musical and cultural cause – looking back, I think it was a little overkill. In 1980, we took a drastic turn musically. We told our producers that we could not continue to make music the same way – we wanted to move forward. I had to make a choice: or I had to starve and die off as a believer of politics – but realizing how corrupt it all is – I thought that we, as a band, still had a lot to experience, especially in terms of music.

What about after 1980?

In 1980, we dove straight into making music, we didn’t want to waste any more time. We were eager to learn and produce. Before we could record, we made our own studio in the house – which took about three years because we didn’t have any money! In this time we released Ta’amulet Al Kouz. Then Toufic left for France in the mid-eighties so it was just me and Elia – we worked as real close friends – all day and all night – except when we fought (but even then it turned out just fine!) Later, we came out with Ta’amoulet el Kouz Bi Tamuz in 1983-4. Eventually, in 1985, we released the cassette version of Hija’a– which was a self-produced work which, looking back, I cherish the most out of all my work I’ve created until now.

You also played guitar on Abu Ali.

Yes! In fact that’s a very funny story. We had flown into Greece to record it and Abu Ali - being a complex and long piece of music - took about a week for everybody to record. I just walked into the studio and recorded my bit in ten minutes! We all had a laugh at that.

What about the nineties?

In 1992 I went to Canada – and had the chance to stay there and really pursue a musical career. I showed my music to many people there and it was really well-received. I had to make a choice: I either had to go back to Lebanon or to stay in Canada. I came back to Lebanon for my kids. But looking back, it was, and still is, hard working in Lebanon – I also taught high school philosophy for twenty-five years and retired from that recently. Eventually in 2000, I decided to take a trip to Nepal and found it to be one of the most beautiful countries I had ever visited. I began buying merchandise from there – all kinds of curiosities – and opened up the current store I am running in Mar Elias street.

As the conversation drew to a close, Issam played a final track. What emerged from the speakers was quietly arresting: a new composition anchored by the kanun, woven together with oud, guitar, understated female backing vocals, and a dense, confident bass line. When asked about future releases, he paused before answering, “Yes, we all have different goals and feelings now. We see things differently”.

Readers are encouraged to explore the legacy of Ferkat Al Ard and Issam Hajali’s broader body of work. Ferkat Al Ard’s music is available on SoundCloud and YouTube; searching for “فرقة الأرض” leads to their full album Oghneya. Hajali’s contributions can also be heard on Rima Khcheich’s albums Yalalalli and Falak, as well as on Tania Saleh’s recent release, A Few Images. A new album by Hajali is currently in progress, promising a thoughtful addition to an already influential catalog. Beyond music, he also runs a delightful store in Mar Elias.

It is also worth noting the trajectory of Toufic Farroukh, an original member of Ferkat Al Ard who went on to establish himself as a respected musician in his own right. Based in France since the mid-1980s, Farroukh continues to release albums and returns regularly to Lebanon. The band remain close friends.

-

This interview was originally published in AUB Outlook on March 8, 2016.