On a late summer afternoon in 2019, an engineer stood in the open courtyard of a house he was overseeing and looked up at the sky. Lebanon, at the time, was gripped by nationwide protests, a deepening economic crisis, and a rapidly devaluing currency. Possibilities — financial and material alike — were narrowing.

He lowered his gaze, turned to his perplexed foreman, and said quietly, “I’ve found the solution.”

The brief was precise. During renovations, the house’s owner had removed the original red-tile pitched roof, leaving the courtyard exposed. In its place, he required a series of louvered sunshades: 8.2 meters long, spaced half a meter apart, and fully cantilevered from wall to wall. They were to provide shade and privacy from neighboring buildings, appear natural, and be constructed entirely of wood. Any intervention had to be structurally sound while remaining sympathetic to the house’s historical character.

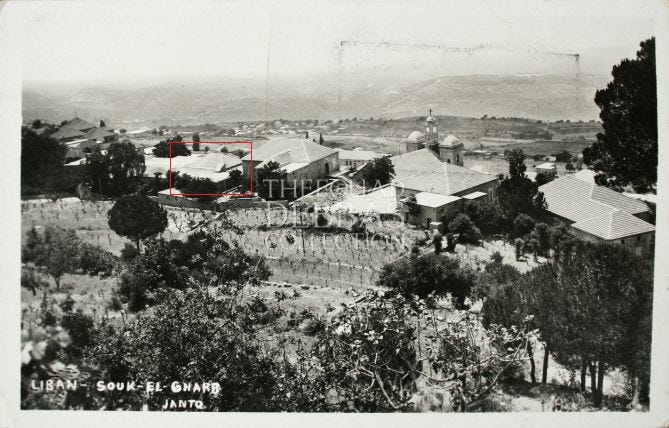

The house had once belonged to Samia Baroody Corm — Lebanese cultural figure, beauty queen, and socialite — and her husband Charles Corm, who, following a meeting with Henry Ford, secured the Ford Motor Company dealership for the Greater Middle East at a time when Ford was the world’s sole automobile manufacturer. Their son, Hiram Corm, was now restoring the property as a retreat for his children and grandchildren, in Souk al-Gharb, a hill town on the outskirts of Beirut.

“What solution, sir?” the foreman asked.

“Wooden electricity poles,” the engineer replied.

The foreman’s expression changed instantly. “I’ve been trying to think of something,” he said, “that could work. But where would we find them?”

By then, Lebanon’s electrical infrastructure had long transitioned to steel utility poles. The engineer’s search led him to a contractor specializing in carpentry for coastal environments — cafés, boardwalks, and waterfront installations requiring rigorous waterproofing. The contractor revealed that he still had a stock of decommissioned wooden electricity poles made of Finnish pine (Pinus sylvestris), originally imported by the Lebanese government decades earlier and later replaced by steel.

Ten poles were ordered.

To install them, threaded bolts were embedded into the tops of the courtyard walls. Corresponding cavities were drilled into the louvers, filled with structural adhesive, and slipped over the bolts, creating a concealed connection. The timber was then sealed with multiple layers of waterproofing membranes to ensure longevity.

When the work was complete, the engineer recognized that the resulting structure was more than a practical solution. The louvers stood as a quiet testament to resilience and reuse — to sustainability born of constraint, and to an engineering gesture that bridged time, place, and nations.

-

This article was originally published in Civil + Structural Engineer Magazine on August 25, 2024.