Ferdinando Manetti — The Italian Painter Who Helped Shape Lebanese Modern Art

By Ralph I. Hage, Editor

The Waterlilies of Basta

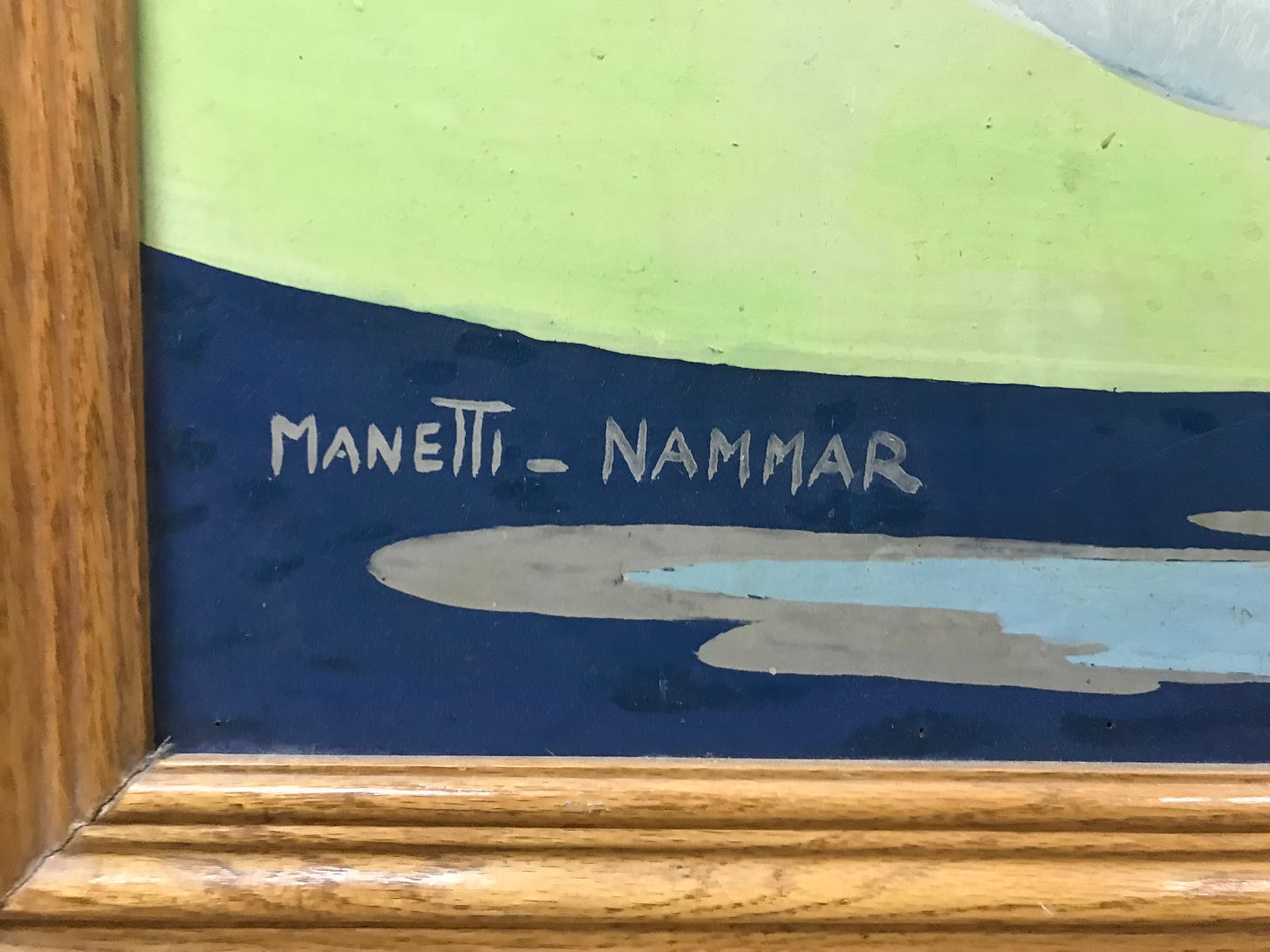

Years ago, I first encountered the name ‘Manetti’ while shopping in Basta, one of Lebanon’s famous antique districts. Behind a pile of furniture, a painting peeked out, its blue, green, and silver brushwork shimmering in the corner of a wooden frame. In its corner, two signatures placed side by side read: ‘Manetti-Nammar.’

I negotiated with the dealer and bought the nearly ten-foot long painting on the spot. After receiving the payment, he admitted he was happy to get rid of it — “nobody wanted it because it wouldn’t fit on their living room walls!”

This painting does not belong on a living room wall, I thought, it belongs in a more public space. I arranged for a truck to drop it off at our office’s storage space where it sat quietly for months while I travelled for work. While abroad, I told my father that I had bought a special painting but hadn’t taken a picture of it. When we returned to Beirut, my father and I turned the storage light on and took a closer look at the painting — yes, it was something special indeed. But who were the artists?

There was very little information online about Ferdinando Manetti (also referred to as Fernando or Nando), and even less about Nammar — so I started with his story.

Nicolas Nammar

Nammar, though less well-known than his contemporaries, was a pivotal figure in Lebanon’s artistic evolution. Born in Beirut in 1925, he trained in Europe before returning to his homeland in 1953. His work blended classical techniques with a growing interest in modern art, and he became one of the founding members of Lebanon’s most important art institution, the Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts (ALBA).

His style veered toward classical draftsmanship with a delicate handling of light — a sensibility that likely resonated with Manetti’s structure-driven approach.

Their collaboration on Waterlilies is unusual in the context of the period. Joint signatures were rare among Lebanese painters then, suggesting that the work may have served a specific public commission or pedagogical purpose. Nammar’s participation hints that this painting might have been both a dialogue between teacher and student and a reflection of a friendship shaped by the lively Beirut art circles of the 1940s and 50s.

While it is difficult to distinguish exactly which passages belong to which hand, the more ethereal brushwork in the water’s surface and some of the softer transitions in the lily pads bear similarities to Nammar’s later work. But to better understand the collaboration, I traced the eventful journey of Ferdinando Manetti.

Ferdinando Manetti

After some research, I discovered that Manetti was born in 1899 in San Giminiano, Italy. He began his studies in painting, focusing on fresco techniques. By the late 1930s, he had moved to Ain Karem in Palestine to create religious artworks.

Ain Karem is known as the birthplace of John the Baptist and is where the Virgin Mary visited her cousin Elizabeth who lived there. During World War II, for reasons unknown, Manetti was imprisoned by the British in 1940. Four years later in 1944, he was allowed to return and paint in the Church of the Visitation in the village.

The Madonna of the Prickly Pear Cactus

The apse of the Church of the Visitation unfolds like a triptych, with Manetti’s Madonna of the Magnificat at its center. The Virgin stands in a golden, hilly landscape, flanked by two large prickly pear cactus bushes and surrounded by small desert flowers. At her feet kneel the Franciscan patrons of the church, while a choir of angels hovers above. Dressed in a royal red gown and blue mantle, the Madonna embodies both grace and divinity.

Manetti’s vision feels strikingly modern — a moment of revelation rendered in vivid form. His decision to replace the traditional palms and olive trees of the local environment with the prickly pear cactus is unusual and symbolic. A plant with no tradition in Christian art, the cactus may reflect the desert landscape Manetti knew during his years in a British detention camp. Thus, the mural becomes a personal emblem of endurance, gratitude, and faith.

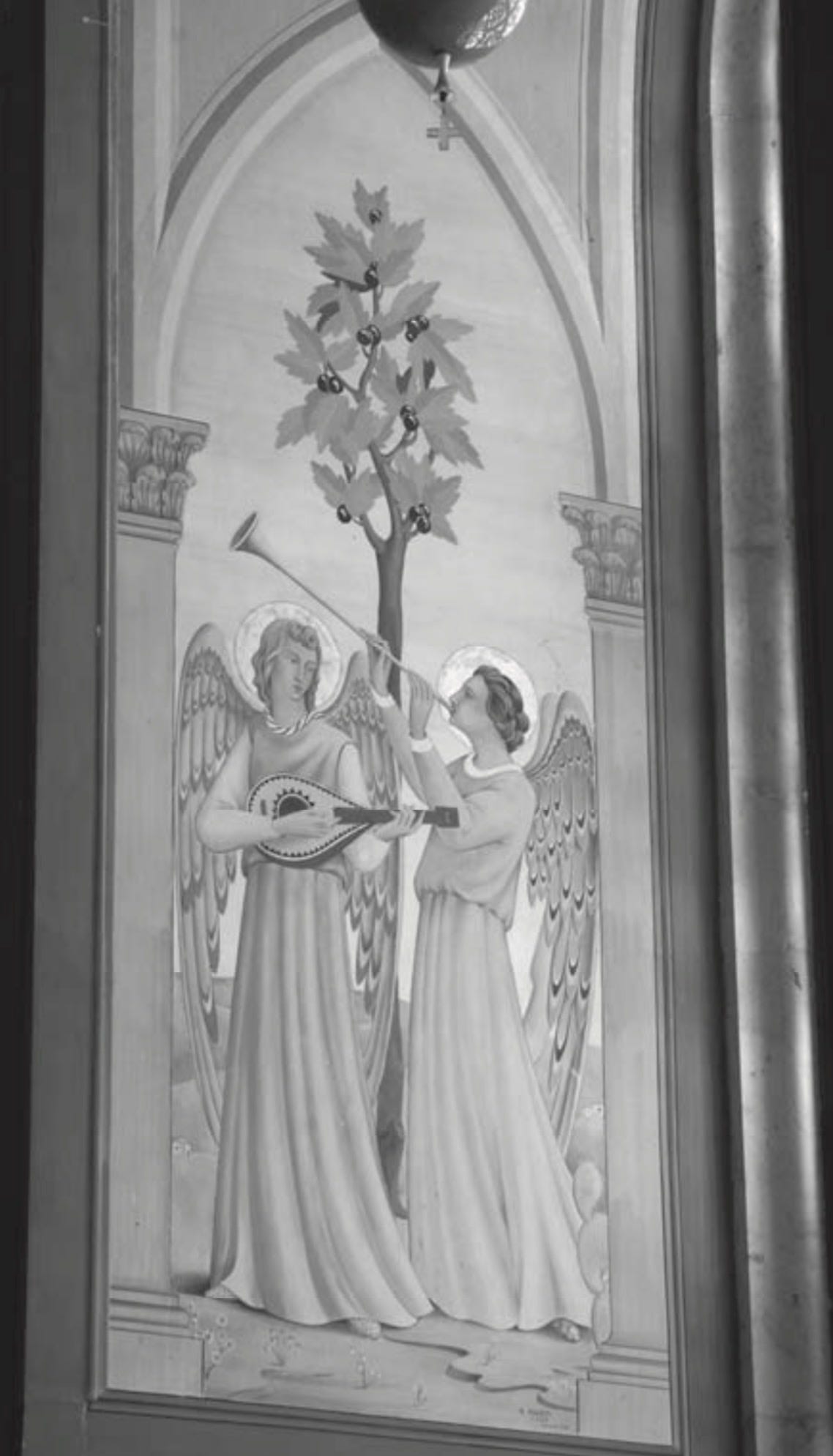

This dialogue between the sacred and the earthly continues on the north wall, where ten pairs of angels appear to stand on yellow desert sands. Their bright wings and flowing robes evoke heaven, yet they are rooted in the same desert world as the Madonna. In one pair, a guitarist and a trumpeter stand beside a small cactus, both with golden halos that glisten in the light, next to which Manetti signed his name and the date, 1944 — the year of his liberation. The cactus here becomes his symbolic signature, a quiet expression of his own renewal and freedom.

Smaller images of the cactus appear throughout the church — in Biagetti’s façade mosaic of the Madonna arriving at Ain Karem, and in the upper church floor mosaics among animals and plants. This recurring motif, with its red fruit and resilient form, was likely a deliberate choice, expressing both artistic joy and spiritual gratitude.

His Move to Beirut, Lebanon

After completing his work at the Church of the Visitation in Ain Karem in 1946, Manetti moved to Beirut.

In the years following World War II, Beirut’s art scene was at a crossroads. The city had become a meeting point for Levantine, Armenian, and European artists, each bringing their own vision and style. The atmosphere was electric — galleries were sparse, but intellectual circles were thriving, and Beirut was quickly becoming the cultural capital of the region. In this environment, the Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts (ALBA) emerged as a key institution for training a new generation of artists, many of whom would go on to define modern Lebanese art. Manetti, with his classical training and emphasis on form, found himself teaching students there who were beginning to explore abstraction and the European avant-garde.

In some ways, he was a bridge between the old and the new, providing a grounding in the fundamentals while also encouraging experimentation. His teaching culminated in a 1963 exhibition at the Bristol Hotel, and he was preparing another show in Italy when he passed away in Beirut on March 18, 1964.

Known for a poetic realism, Manetti contrasted with fellow Lebanese artist Cesar Gemayel, whose thick, vibrant oils celebrated color and form. Manetti’s work, on the other hand, followed the Italian tradition of subtle painting, seeking order and refined exuberance. This discipline made him a compelling mentor to students such as Shafic Abboud, Huguette Caland, Paul Guiragossian, Yvette Achkar, and Jean Khalifé, many of whom became leading figures in Lebanese art themselves.

The artists he mentored would go on to forge their own paths in Paris and beyond, but they always carried with them Manetti’s disciplined approach to painting.

From Desert Bloom to Waterlily Stillness

Manetti and Nammar’s later Waterlilies continues the visual language Manetti developed in his Madonna of the Magnificat. Like the desert cactuses surrounding the Madonna, the lilies symbolize renewal and quiet strength, thriving in their natural environment while carrying religious symbolism.

The composition reflects Manetti’s love of rhythm and balance, and the size of the painting is reminiscent of wall murals. A colleague of mine suggested that the painting was likely once located at the entrance of a residential building or a public space like a cinema or restaurant — which made sense considering its scale. The evenly spaced lilies echo the structured arrangements of his earlier apse, while the cool blues and greens replace the desert golds without losing harmony or calm. The silver strokes of the water ripples, reminiscent of the golden halos of Ain Karem, reveal a secret feature of the painting — they glisten in the moonlight. Their shapes also echo the outline of the desert rocks of the Madonna of the Prickly Pear Cactus.

Though less overtly religious, the work retains the meditative spirit of his sacred scenes. Nature becomes a language of devotion — whether a cactus rising from sand or a lily floating on water, each image speaks of innocence, faith, and beauty.

Together, these works trace Manetti’s evolution from sacred narrative to reflective meditation. The Madonna of the Prickly Pear Cactus celebrates resilience and devotion, while Waterlilies transforms that same sensibility into quiet contemplation, showing his enduring ability to find the divine in nature.

Mario Manetti, The Artist’s Son

In 2021, I reached out to the artist’s son, Mario Manetti, with a picture of the painting. He shared some of his insights with me:

“We lived for a large part of our life in Lebanon, at that time one of the most pleasant countries to live in. My father taught painting at the Lebanese Academy of Fine Arts where most Lebanese modern painters learned the art of painting. Nicolas Nammar was one of his students.”

That confirmed the mystery of the second signature — it reflected the hand of Nicolas Nammar, the respected founder and president of the Association for Lebanese Artists and Sculptors. He took a young Aref El Rayess under his wing, and they eventually collaborated to establish the Institute of Fine Arts at the Lebanese University in 1963. He would become a key figure in shaping Lebanon’s postwar art scene, mentoring the next generation of modern painters — but that subject deserves its own article.

Later, Mario expressed appreciation for my sending a picture of the painting that his father had painted over half a century earlier. And in the end, we hung the painting in the center of our Beirut office — it didn’t belong on the living room wall.